Archive for the ‘Film’ Category

« Older EntriesNewer Entries »

Arrival

Friday, November 11th, 2016—FilmArrival (USA 2016, Drama/Mystery/Sci-Fi), Writer: Eric Heisserer; Director: Denis Villeneuve

I write this piece with such a heavy heart. It has been a dark, difficult week.

It feels sadly fitting that the great, the legendary Leonard Cohen, who left us days ago, named his most recent album You Want It Darker. We have gotten that.

As I read about people celebrating what they see as a “white victory” south of the border, and hear of the planned changes by the upcoming administration to repeal so much progress, to weaken environmental protection (when we’ve already been told by the experts that we hadn’t been doing enough)…

It’s hard to know what to do next. Yet while some of the acts taking place right now are indefensible, there’s another side to all of this. This election, and the climate that made it possible, has illuminated the gaps, the wounds, the divides, and proven the need for better understanding, on all parts. Because we have clearly not been speaking the same language.

In Cohen’s death, we lost one of our most gifted artists. But I take solace in the fact that another talented, highly reflective Canadian artist is still hard at work, revealing elements of our true nature so we ourselves can take a good look and, with hope, do better.

Denis Villeneuve is one of the best directors working today. He has a facility for making films that examine the world around us. Perhaps more importantly, he has the desire to do so.

From Incendies to Enemy, Prisoners to Sicario, Villeneuve’s work has explored current events and social dynamics, and always made the effort to understand the human condition. He eschews gratuitous violence, encourages female empowerment and injects his artistic sensibilities into every film he makes.

And he does all this while delivering gripping entertainment. If his movies continue to be welcomed by the mainstream, we’ll all be the better for it.

Villeneuve’s latest film is so timely and so poignant that it hurts a bit to watch. But sometimes that’s how the truth works. And what a stunning piece of honesty it is.

Arrival is based on Story of Your Life, the brilliant 2000 Nebula Award-winning short story by Ted Chiang about language, love and time. In the film, 12 alien crafts descend from the skies, hovering over various points across the globe. One of those points is Montana, where linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is summoned by Colonel Weber (Forest Whitaker) to join mathematician Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner) in deciphering the alien language and learning to communicate with the craft’s inhabitants, called heptapods. Specifically, Louise is tasked with determining their purpose on Earth.

Nearly from beginning to end, Arrival is fraught with tension. As teams at each of the 12 points race to communicate with the heptapods, concern grows over when the exchanges will grow violent—that is, when governments will unilaterally decide to attack the heptapods. Far from cooperating, nations examining the crafts start shutting each other out, guarding their discoveries like trade secrets.

There is also, of course, the more immediate fear over Louise and Ian’s safety, as they work tirelessly to progress in their communications. Villeneuve and cinematographer Bradford Young (A Most Violent Year) gorgeously capture every one of Louise and Ian’s dimly lit, eerie but exquisite contacts with the heptapods—so evocatively presented by production designer Patrice Vermette (The Young Victoria, Enemy, Prisoners, Sicario). As envisioned by the filmmakers, the creatures are stunning, with spindly bodies looking more like giant, delicate, dexterous seven-fingered hands than any earthly body.

The heptapods’ graceful, fluid movements are mirrored by the flowing fog that pours over the Montana site when Louise and the crew first approach the craft. As they move in closer to the elegant, oblong oval poised above ground, surrounded by misty mountains, it’s impossible not to be affected by the beauty.

That clash, that collision between unknown menace and hypnotic allure, is punctuated by Jóhann Jóhannsson’s enigmatic score. Jóhannsson is the genius behind Sicario’s pulsing soundtrack, and his music plays an equally powerful, defining role in Arrival. His score is spare, spooky and otherworldly, at times melodic, others metallic and almost grinding, but always deeply poetic and affecting, the perfect mouthpiece for Villeneuve, Vermette and Young’s visuals.

Together, these powerhouse artists maintain a tightrope of tension throughout the film. But you’re never alienated from the story’s human heart because Villeneuve and the extraordinary Adams always keep Louise at the forefront.

Louise is haunted by memories of her deceased daughter, and her work with the heptapods frequently triggers words and visions from their time together. As she becomes more familiar with the heptapods’ language, Louise begins to understand that time doesn’t exist for them the way it does for us. Their language, like their physics, is out of this world.

The heptapods use a semasiographic writing system that conveys meaning without reference to speech. It isn’t confined by linearity the way spoken words are. Instead, it relies on complex symbols (brought beautifully to visual life in smoky, ink-link graphics that can be drawn into the air), which require knowing in advance everything you want to say before writing a single symbol. Once you truly learn the language, time will cease to function as it did before; you’ll be able to see the interconnection between past, present and future.

Arrival’s story structure reflects its inventive ideas about language. It weaves through chronology in an unconventional way, asking us to piece it all together at the end. Chiang did this so effectively in his short story, and screenwriter Eric Heisserer does him justice with his adaptation. Heisserer’s screenplay streamlines and consolidates where the medium demands it, but maintains the original story’s power and message. It also makes a stronger case about the need for global unity and the dangers of miscommunication, making the film all the more meaningful today.

At one point in Arrival, Louise explains a linguistic theory about how language shapes the way we think and perceive the world around us. It can enlighten. It can also enclose. In other words: the words we use matter. That’s something we dearly need to remember as we face an increase in the language of hate and divisiveness.

I’d been looking forward to seeing Arrival since last year. I’ll happily see any Denis Villeneuve film, but after reading Story of Your Life, I was even more excited for this one. I had no idea these would be the circumstances under which I’d be watching Arrival—that the film would be so significant on so many fronts. But whether forlorn or uplifting, its relevance only adds to its importance.

See Arrival because it’s a wonderful work of art made by some of the greatest filmmakers of our time. Because it’s intelligent, thought-provoking and gripping. And because it is, ultimately, about the value of life, no matter what the outcome, and the fact that life never really ends as long as we remember it, and that it is still—always—worth looking forward, creating new life and cherishing it for however long we hold it.

In his latest album’s title song, Leonard Cohen sings this:

There’s a lover in the story / But the story’s still the same / There’s a lullaby for suffering / And a paradox to blame / But it’s written in the scriptures / And it’s not some idle claim / You want it darker / We kill the flame

But from earlier records, those that cannot be erased, there’s also this:

Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There’s a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in

I’ve seen the nations rise and fall / I’ve heard their stories, heard them all / But love’s the only engine of survival

Hallelujah.

* * *

Thank you to Paramount for the advance ticket to Arrival.

For more on the great work of Denis Villeneuve, see my Kickass Canadians article.

The Babadook

Wednesday, August 24th, 2016—FilmThe Babadook (Australia/Canada 2014, Horror), Writer/Director: Jennifer Kent

I took my time getting to The Babadook, but this one is definitely a case of “better late than never.”

Horror is a genre I tend to avoid. I hate gratuitous violence and don’t like being scared just for the hell of it. The Babadook is horror I can handle; instead of cutting up bodies, it dissects psyches.

Specifically, the film looks at the strained relationship between widowed mother Amelia (played beautifully by Essie Davis) and her son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Amelia’s husband died in a car accident while driving her to the hospital for Samuel’s birth. Six years later, she still can’t bear to celebrate Samuel’s birthday on its proper day.

Things are strained in Amelia’s household to begin with. Both she and Samuel are troubled sleepers plagued by nightmares. Amelia dreams about her husband’s accident. But Samuel is haunted by a faceless monster. He can’t put a name to it; he just knows it’s there.

Every night, Samuel and his mother go through the ritual of inspecting his closet, peering beneath under his bed. And during the day, he practises magic tricks and fires off homemade weapons: “I’ll kill the monster when it comes, I’ll smash its head in!”

It’s all an attempt to protect himself and his mother from whatever darkness is descending, but it only adds to the mounting pressure on Amelia. Samuel is unruly, uncontrollable. He gets expelled from elementary school for endangering other children. His manic energy and incessant calls of “Mommm! Mahmmmmmmm!!!!” wear on her nerves, already fraught from chronic sleep deprivation. She’s quick to snap, even when he simply hugs her too hard.

And then we meet Mister Babadook. “If it’s in a word or in a look, you can’t get rid of the Babadook.” Samuel finds him in an authorless pop-up book his mother hasn’t seen before; it’s been sitting on the shelf, out of sight, perhaps not out of mind.

The book is a brilliant way of introducing the film’s demon—a dark man in a top hat and black cloak who kills children in their beds. With its chilling yet artful illustrations and eerie, poetic writing, Mister Babadook creeps into the viewer’s psyche just as much it does Amelia’s and Samuel’s.

“You start to change when I get in, the Babadook growing right under your skin.”

Amelia quickly puts an end to the story, but it’s too late; Samuel knows what’s coming. As his obsession with building weapons grows, so does Amelia’s anger and frustration with her son. She insists that the monster isn’t real, but he’s certain that it’s only getting closer.

He isn’t wrong. The question is: Where does the Babadook truly reside? In their closets, cupboards and basement? In Amelia’s mind? Maybe in both.

That, to me, is the most intriguing part of the movie—its exploration of fantasy and reality, sanity and delusion. It reminded me a bit of Take Shelter, in how it asks the audience to decide, at least for a time, whether the threat is real or imagined, and in how it throws light (and shadow) on mental illness.

The Babadook isn’t afraid to show us something really scary, and its impact is profound and disturbing. In place of cheap thrills and gore, it uses imaginative, often abstract visuals. The film does a lot with its soundscape, too; whenever the Babadook stirs, we hear a chilling mix of repetitive sounds that are almost familiar, almost identifiable, like crickets at night or the electrical buzz of an unstable light bulb about to burn out.

Amelia tries to silence the noises by destroying the book, but the more drastic her attempts to bury it, the more fiercely it returns. “The more you deny me, the stronger I get.”

The Babadook becomes a metaphor for Amelia’s grief and depression. She’s stuck in the moment of her husband’s death, unable to process her emotions. She’s also suffocated by the guilt of blaming Samuel and the unease of her son standing in as her only companion.

Their relationship never crosses any sexual lines, but there’s a tangible discomfort from Amelia. At one point, Samuel bursts in on her in the night, interrupting an intimate moment while she’s alone in bed (there’s that electrical buzzing sound again…), and it highlights the strangeness of their dynamic—how Samuel’s birth brought about her husband’s death, effectively replacing one with the other.

As the world grows ever darker for Amelia and Samuel, we’re forced to wonder exactly what’s true. Amelia is being driven into psychosis through depression and sleep deprivation. And yet there he is, Mister Babadook—lurking in corners, scuttling and spattering across the ceiling like an insect or an inkblot, morphing, indeterminate, a Rorschach test. What is he? What is it? What does it mean to Amelia? What does it mean to us? And which demon would be harder to exorcise: the supernatural or the psychological?

The Babadook shows us that we don’t always have to eradicate our demons. Sometimes it’s enough to be aware of their presence and learn how to manage them. Because sometimes these things—in the shadows, in the mind—never really go away.

Sleeping Giant

Saturday, April 30th, 2016—FilmSleeping Giant (Canada 2015, Adventure/Drama), Writers: Andrew Cividino, Blain Watters, Aaron Yeger; Director: Andrew Cividino

When the credits rolled on Sleeping Giant last night, the audience was completely silent for a beat or two, before erupting into applause. That’s the impact this movie has. It’s raw, real and chilling, and it gets into your head—and heart—in a way that few films do.

Sleeping Giant is adapted from writer/director Andrew Cividino’s 2014 short film of the same name. Set in Thunder Bay, Ontario, the movie spends a few summer weeks hanging out with Adam (Jackson Martin), Riley (Reece Moffett) and Nate (Nick Serino), three teens cottaging with their families on the shores of Lake Superior, near the majestic Sleeping Giant Provincial Park.

Adam stays with his well-to-do parents in their spacious abode. Riley and Nate, cousins, crash at a much smaller pad belonging to Nate’s grandma (Rita Serino). The three boys’ disparate backgrounds go beyond socioeconomics. Adam is nurtured and sheltered, for better and for worse; he’s more reserved, better mannered. Riley and Nate, on the other hand, talk rough and play rough. They’re destructive and violent with their actions and their words—especially Nate, who constantly makes a show of being stronger, raunchier and more experienced than the others.

Sleeping Giant has a few twists to its story, involving Adam’s less-than-honourable father (David Disher), and his friend Taylor (Katelyn McKerracher), an attractive teen girl who becomes a point of contention between him and Riley. But it’s mainly a summer coming-of-age story, with the three boys standing atop a pivotal cliff, deciding which way to jump—what kind of adults they will become.

A lot of this film is terrifying to watch. Seeing the trouble the boys get into, being privy to their often volatile thought processes, realizing how malleable they are; it’s a sobering reminder of the past, of how wrong things could have gone, and of what could happen in the future, what’s going on right now. It also makes me grateful for the grounded, responsible teens in my own life. Because in Sleeping Giant, things take a dive for the worse.

Walking into the theatre last night, the title of The Weeknd’s album Beauty Behind the Madness came to mind. The film does venture into that territory, or perhaps also the madness behind the beauty. These boys have potential; even Nate shows glimpses of good qualities, like intelligence and honesty, and of wanting to do more with himself. They’re at such a delicate age, each one wrestling with their own sleeping giant—id vs. ego, and the submerged darkness that threatens to take over when their burgeoning identities are threatened.

Adam, Riley and Nate don’t really know who they are yet. The film even suggests, tacitly, that Adam may be questioning his sexuality, with its lingering shots of Adam and Riley tussling, or Adam’s lingering gaze that often favours Riley over Taylor.

Watching Sleeping Giant, it was hard not to reflect on my own coming-of-age movie, Sight Lines, a short that was shot in the summer of 2002 around 1000 Islands in Gananoque, Ontario. Not to suggest that my movie is on par with Cividino’s, but it shares many elements with Sleeping Giant, from 13-year-old Fletcher’s (David Coomber) false bravado about drugs and sexual experience, and his destructive tendencies (both idle and pointed), to the cliff-jumping scene.

There are certain shared experiences about being a young teen in Canada, and about cottage living, that Cividino really captures in Sleeping Giant, making the film easy to relate to.

A large part of the credit for this goes to the extraordinary performances from the three leads. Moffett and Serino are real-life cousins, reprising their roles from the short version of Sleeping Giant. They have no prior acting experience, and perhaps because of that, achieve very real, seemingly improvised delivery. (In fact, much of the cast features non-actors or first-time actors, including Moffett and Serino’s actual grandmother as Nate’s grandma, to good effect.) Martin, who had already wet his feet in the acting world, still arrives at the same nuance and intense realism, bringing incredible subtly to Adam as he experiments with the boundaries of honesty and manipulation, compassion and cruelty.

It’s hard not to notice the contrast between the youth’s naturalistic performances and the stilted delivery from some of the adult actors, most notably Disher (ironically, the most experienced of the performers). Adam’s dad is a real dick, to use the kids’ lingo. He comments on Taylor being “new and improved” and advises 15-year-old Adam to “tap that” while the opportunity is still available. He also makes lame attempts to appear cool in front of Adam’s friends. So I wondered at times if Cividino directed Disher to deliver the awkward performance he does, to make him even less relatable or likeable.

I don’t know about that. But whatever the case, Disher’s relatively weak performance is one of the few detractions from an otherwise successful film.

From the opening sequence that surveys Sleeping Giant Provincial Park to the tune of Bruce Peninsula’s pulsing, foreboding score, to a perfect final moment that says everything without uttering a word—the ending that left the audience speechless—Sleeping Giant is imposing, impressive and important, as a work of art and a reflection of humanity.

For more insights into the film and how it was made, check out Cinemablographer’s recent interview with Cividino.

* * *

This post is dedicated to MJP, who introduced me to Thunder Bay and who works hard to help youth navigate the perils of their own sleeping giants.

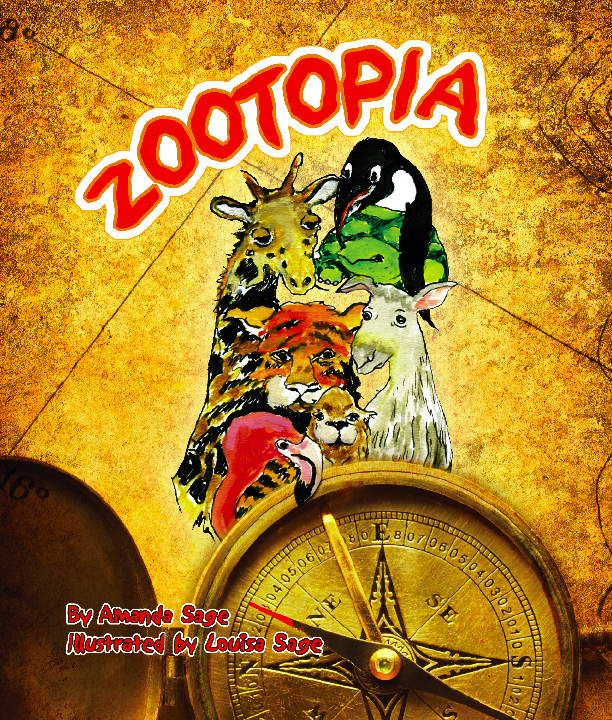

Zootopia (feat. David Walberg)

Thursday, April 7th, 2016—FilmZootopia (USA 2016, Animation/Action/Adventure), Writers: Jared Bush, Phil Johnston; Directors: Byron Howard, Rich Moore, Jared Bush

It’s not often I get to review a movie with one of my three nephews after having watched it together. They’re not from around here, so when we do team up, we all watch the movies separately and then have a chat.

So far, all three boys (Jon, Isaac and David) helped out with The Lego Movie, Jon and I covered The Hunger Games, and he and Isaac both joined me for The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Parts 1 & 2 and Divergent.

This Zootopia review is extra-special to me because I got to take my youngest nephew, eight-year-old David, to see the Disney animated movie while he was visiting. Oh yeah, and also because it steals I mean shares the title of the book I wrote for David in 2010 through my publishing shingle, Wonderpress. (I wasn’t playing favourites; I also wrote Dinostory for Jon and Astrorocket for Isaac.)

We both really enjoyed Zootopia (the movie—though we’re partial to the book, too). Here’s the scene: It’s thousands of years since mammal predators and prey had any trouble co-existing, and a keen young bunny named Judy Hopps (Ginnifer Goodwin) is determined to make her mark in a world where “anyone can be anything.”

Judy bounds out of her hometown, Bunnyburrow, to become the very first bunny cop at the Zootopia Police Department (ZPD). Officer Hopps takes her place alongside a menagerie of other animals, including a buffalo (Chief Bogo, perfectly voiced by Idris Elba), a rhino (Officer McHorn) and a donut-gulping cheetah (Officer Clawhauser, voiced by Nate Torrence). Judy’s relatively small stature doesn’t bode well for her career prospects; while everyone else gets juicy assignments, she’s stuck with parking ticket duty.

Judy tackles her role as meter maid with the same zeal that led her out of the carrot patch and into the sprawling mammal metropolis of Zootopia. But it isn’t long before she scrambles her way onto the city’s biggest case: the 14 missing mammals—all predators. Judy enlists the assistance of Nick Wilde (Jason Bateman), a wily fox and even wilier con artist she’s able to hustle into helping her.

What follows is an interesting examination of the dangers of judging animals by their species, holding pre-conceived notions about others, and prescribing expectations.

When Judy and Nick discover that the missing predators have all gone savage, Zootopia is thrown into unrest, with prey casting sidelong glances at predators. Not that everything was idyllic before the savagery; Judy never reports to work without her can of fox spray, a holdover from her parents’ mistrust of foxes and a frightening encounter from her childhood.

Zootopia’s premise is smart, timely and delivered in a very well wrapped package: Bright, bold animations with meticulous attention to detail (David especially liked the way they moved); a tight, witty, highly polished script; and an inventive world in which the animals can roam and romp.

Zootopia consists of a range of ecologically diverse districts, like Sahara Square, Tundratown and Rainforest District. Little Rodentia was especially charming, with its many roadways and overpasses made of clear plastic hamster tubes. “I liked the rodent town,” says David. “There were lots of gerbils!”

The city is built to accommodate all types of mammals. Elephants are served massive (relative to us) ice cream cones served up (somewhat) fresh by the trunkful. Mice scurry through miniature gateways and get dolled up at small-scale (but high-class) hair salons.

“I liked it when the guinea pigs chomped on the Pawpsicles,” says David. So did I; the several-tiny-bites-sized frozen treats are made in molds formed by Chihuahua footprints in the snow.

Zootopia is a playful, inventive place for Judy and Nick to guide us through a study in race (or in this case, species) relations. The messages are clear, but they extend beyond the obvious ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ adage. For example: Be careful what you tell people about themselves; they just might believe it.

The movie does a good job of challenging assumptions, both personal and structural. “It messed around with your expectations,” says David, pointing out a few instances when the story took surprising turns.

I asked him if he thinks all animals—predators and prey—really could get along. “Well, it depends,” says David. “They could get along if they weren’t so smart-mouthed. Like the fox, Nick, you have to admit he was pretty smart-mouthed. But he’s also quick-witted. It’s good to have someone quick-witted around. Or you could just memorize Shakespearean insults like I do. ‘Go to hell for an eternal moment or so.’ That’s from The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

(He actually said that. What a kid.)

David talked a bit more about the film’s central message, and he said something very wise: “No animal really is just one thing. Prey can also be predators—especially humans.”

He’s right. Almost all of us can attack or be attacked.

For an animated children’s film, Zootopia brings a lot to the conversation. As great as it is, though, I thought it missed a couple good opportunities for commentary.

Assistant Mayor Bellwether (Jenny Slate), who is a sheep, remarks that Zootopia is comprised of 90% prey. I expected the movie to draw a parallel to the 99%, with most of the prey being smaller and more vulnerable than the predators. But it didn’t.

Then there was the highly sexualized Gazelle (Shakira), Zootopia’s mammal pop star. We see enough of scantily clad females in everyday media, put in a position where they’re expected to trade in on their bodies for success or recognition; it would have been nice if Disney hadn’t felt the need to ensnare the film’s only icon in a sequined miniskirt and crop top.

I really did like Zootopia, but for a movie so determined to do away with stereotypes, it sure has its share of them. Like the wolves who can’t keep themselves from chiming in once the first howl is released. And the sloths who move at a, well, sloth’s pace.

Mind you, caricaturing sloths leads to a priceless scene at the Department of Mammal Vehicles (DMV) when Judy and Nick drop in to pursue a lead. So, I’m not complaining—just observing.

“The sloths at the DMV were pretty funny,” says David. “It was a good joke.”

In fact, that’s where we first meet David’s favourite character in the movie, Flash the sloth (voiced by Raymond S. Persi).

Zootopia has loads of fun anthropomorphizing the animals, shrewdly reflecting human culture and convention. Judy drew chuckles from the audience when she explains to Officer Clawhauser: “You probably didn’t know, but a bunny can call another bunny cute, but when other animals do it, it’s a little…” Her mortification at seeing animals do yoga naked is also pretty awesome. Or, as David says, “AWKWARD!!!”

After the movie, I asked David whether he’d rather be predator or prey. “Prey. I’d be an elephant. No—a panda. Or a koala.” So, it doesn’t matter if you’re big or small? “Depends who I’m up against. The big ones are more out of control, like I am. That’s a joke.”

David and I both highly recommend this smart-mouthed, fun-loving foray into the animal world. Overall, it’s creative, delightful and clever, and it presents us human animals with some important things to consider.

Oh, and I loved seeing ZTV newscaster Peter Moosebridge, voiced by CBC’s Peter Mansbridge.

And you can buy my version of Zootopia—the children’s book—here.

David aboard the “Zootopia” express

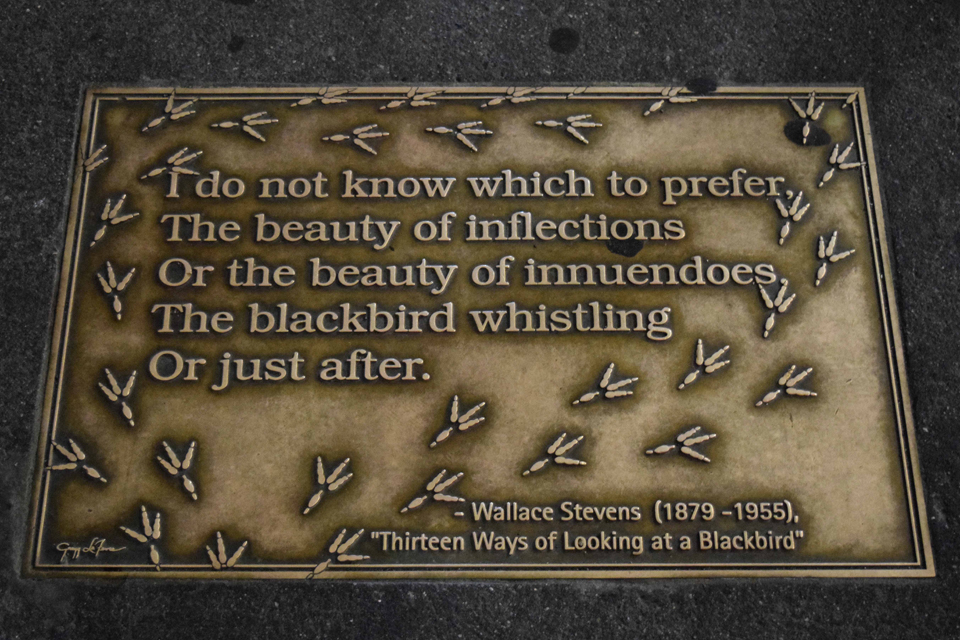

Blackbird (live) & The Crucible (live)

Monday, March 28th, 2016—FilmBlackbird (Belasco Theatre, 2016), Writer: David Harrower; Director: Joe Mantello

The Crucible (Walter Kerr Theatre, 2016), Writer: Arthur Miller; Director: Ivo van Hove

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

I read these words on a plaque, embedded in the sidewalk, shortly after arriving in Manhattan last week. The plaque is one of several lining the way to the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue, but it was this quote, from Wallace Stevens’ poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, that spoke to me. GB and I had tickets to see Blackbird on Broadway, starring Jeff Daniels and Michelle Williams, at the end of our visit and knew it would be one of the trip’s highlights. So, seeing the plaque felt like a fitting welcome to the city.

What I didn’t know then, reading those words, was that the trip would be bookended by a bonus highlight. There was another Broadway show I’d really wanted to see—The Crucible, featuring an extraordinary cast that includes Saoirse Ronan, Ben Whishaw, Sophie Okonedo and Ciarán Hinds. Tickets were pretty pricey, so we initially passed on that play. But while wandering through Central Park that first night in New York, we decided, on a whim, to see if we could get rush tickets.

What we got was so much better than I imagined. We were offered an incredible discount on prime seats: centre orchestra, just a few rows back from the stage, and right beside Sean Penn. It may seem like a silly thing to mention here, but being next to one of the greatest living actors, and someone whose work and films I greatly admire, couldn’t help but amplify the experience of watching such a high caliber cast performing in such an incredible production.

To me, one of the very best things about New York is that it provides a stage for the highest concentration of the world’s most exceptional artists. In Manhattan, on any given day, you have access to performances you just wouldn’t see anywhere else. And this isn’t only on Broadway. While wandering through lower town, we saw a poster for an upcoming talk at a community centre; the speaker was David Mamet. When I lived in New York several years ago, I joined some friends at the last minute for a panel and Q&A at the Irish Arts Center with Gabriel Byrne, Helen Mirren, Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon. There’s always something going on and I find it exhilarating.

So, as we waited for the curtain to rise in the Walter Kerr Theatre, sitting next to Sean Penn, who is easily one of my favourite actors, the point came across loud and clear: Magic happens in New York City, and we happened to be catching an act that evening.

Regardless of your seatmate, The Crucible is an experience worth having. It’s directed by Ivo van Hove, the theatre legend who delivered a highly praised production of Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge on Broadway late last year. Set during the Salem witch trials of the late 1600s, The Crucible was written in the 1950s as a parable about McCarthyism, but it continues to be eerily prophetic, especially in the face of today’s escalating xenophobia and religious discrimination.

John Proctor (Whishaw), the well-meaning husband of Elizabeth Proctor (Okonedo), tests the limits of the old “hell hath no fury” adage when he tries to move past his indiscretion with young Abigail Williams (Ronan). The Proctors former servant, Abigail also dabbles in witchcraft. When the townsfolk suspect her and her friends of ill doing after a few mysterious deaths and some late-night incantations in the woods—in the buff—they turn around to point their fingers at others, including the Proctors. From there, things quickly spiral down the rabbit hole.

The Crucible’s set is spare yet detailed, and dimly lit—glowing candles here, a fiery stovetop there. Among other pieces, it features an ever-present chalkboard in the background, where characters occasionally write commandments or proclamations as the audience is schooled in the dark arts of humanity: judgment, fear, dishonesty, blame.

The play’s music, by celebrated stage and screen composer Philip Glass (The Hours, Fantastic Four), feels almost ambient. It pulses throughout much of the production, sometimes with strings, others with percussion, mostly subdued but nearly always present.

The Crucible’s biggest success comes in the form of its large and highly skilled cast, delivering fine performances all around. It was a privilege to see Ronan (Atonement, The Lovely Bones), a gifted film actor, perform live. It was even more breathtaking to watch Whishaw (The Danish Girl; Q from Skyfall and Spectre) and especially Okonedo (Hotel Rwanda) onstage. They deliver commanding, riveting performances that literally left me shaking after the curtain call.

As good as The Crucible is, Blackbird’s tune is the one that still echoes through my thoughts.

From the moment the play opens, we know that Blackbird is a story about people laid to waste. When the set, a drab meeting room in a bleak office, spins around on a turntable, finally facing us, we see that it’s littered with garbage. The trash bin is overflowing, the table carelessly scattered with leftovers and other remnants. The place is filled with the ruins of exchanges and conversations past; it was abandoned and no one took the time to clean things up.

Into this room, Ray (Daniels)—or Peter, as he’s now known—forcibly marches Una (Williams). Tension is everywhere, beating through their bodies, blasting forth with every word, and it doesn’t let up for the next 90 minutes.

Through Una’s broken words and Ray’s defensive bluster, we soon learn that the pair was sexually involved 15 years ago, when he was 40 and she was only 12. They haven’t seen each other since the fateful night that separated them, when Una was stranded in a suite and Ray was charged for his crime.

Neither has recovered from their three-month affair, though both have tried (and been tried). After serving his sentence, Ray changed his name, found a new job and partner. Una, in desperate bids for both escape and control, pursued a long line of sexual partners, angrily shocking her parents with the details; based on her steady sniffle and erratic body language, she also chased down a few other lines.

I saw Blackbird from a very different vantage point than I did The Crucible. I was perched at the front of the Belasco Theatre’s third-level balcony, looking almost straight down at the stage. It made for a slightly dizzying experience that added to the play’s sense of unease.

Watching Una and Ray, two lost souls crippled by love, anger, shame and betrayal, frantically trying to wrench themselves free of the pain, is an intense experience. Although there’s no denying how wrong their involvement was, Ray and Una did love each other; perhaps they still do. But in the aftermath, the only way they found to move forward was in darkness.

Ray’s life, as Peter, is a lie.

And Una. Una lived through public and private humiliation. Painted as both a temptress (with “suspiciously adult yearnings”) and a victim, she was repeatedly told that the love she thought Ray had for her was driven only by the sick desires of a dangerous and calculating predator. For nearly two decades, she was left to relive Ray’s final words to her, their final moments together, over and over, like a sleepless child lying in bed after the lights have gone out, with no one to talk to, no one to comfort her. Nothing there but memory and imaginings, both so easily distorted.

Daniels delivers a strong, solid performance. But Williams blew me away. She has been wonderful so many times before (Blue Valentine, Take This Waltz). As Una, she transforms herself. Her body is electric, her movements frenetic. I didn’t recognize her voice; at times, she practically growls rather than speaks.

I wish I could see Blackbird again, from another perspective, to get another glimpse—a closer view, but also just a different view, to see how the actors play the story out on another night, how they might change the key for the often-lyrical dialogue they deliver.

There’s very little music in Blackbird; I recall only a few strains coming through to punctuate certain moments. But after the actors leave the stage, once the damage is done, we’re left with the most perfect song—9 Crimes by Damien Rice:

Leave me out with the waste

This is not what I do

It’s the wrong kind of place

To be thinking of you…

It’s a small crime

And I’ve got no excuse…

Is that alright?

Is that alright?

Is that alright with you?

No.

After seeing Blackbird, on the way back to our hotel, we walked again down Library Way, revisiting the plaque I’d seen on our first night. There, on a misty, mystical night—our last in New York—I read Stevens’ emblazoned words once more. This time, revelling in the remembering of such a powerful play, the words echoed even louder:

I do not know which to prefer…

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

* * *

The Crucible is currently in previews; it opens March 31, 2016 and runs until July 17. Blackbird runs until June 11. I hope you have the opportunity to see both.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Parts 1 & 2 (feat. Isaac and Jonathan Walberg)

Monday, December 14th, 2015—FilmThe Hunger Games: Mockingjay Parts 1 & 2 (USA 2014/2015, Adventure/Sci-Fi), Writers: Peter Craig, Danny Strong; Director: Francis Lawrence

[Spoiler Alert: This is a joint review of Parts 1 and 2 of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay. I don’t give away any key plot points from the second part, but I do reveal what happens at the end of the first. Proceed with caution!]

Here we are, back for the final installment of The Hunger Games reviews with my nephews.

If you’ve been following this blog, you’ll know I started reviewing the series, based on the books by Suzanne Collins, at the suggestion of my eldest nephew, Jon (now 13). We jointly reviewed The Hunger Games, and my second nephew, Isaac (now 12), joined us in reviewing The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.

Now all three of us are back for the third and final review, a joint write-up of Parts 1 and 2 of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay.

To recap, The Hunger Games films are set in a future world where the wealthy rule from the Capitol and the rest live in varying states of squalor and unrest, in Districts 1 through 13. For three quarters of a century, two children from each district have been offered up each year as tributes to fight to the death in a televised reminder of the Capitol’s power—and fury.

The first two films show Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) and Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson) competing in the 74th and 75th Hunger Games, on behalf of their District 12. Having emerged as victors the first time around, their “reward” is to face off against the victors from games past for the Quarter Quell. But things don’t go as planned for the Gamemakers, and Katniss is rescued from the 75th Games by rebels and transported to District 13.

This is where Mockingjay picks up. Katniss, still in the throes of post-traumatic stress disorder, is being persuaded by President Alma Coin (the always wonderful Julianne Moore) and former Head Gamemaker Plutarch Heavensbee (the equally wonderful, and tragically departed, Philip Seymour Hoffman) to rally the rebels and wage war against the Capitol.

While Katniss was retrieved from the 75th Hunger Games arena, Peeta was captured by the Capitol, who torture him, hijack him (a form of drug-induced brainwashing) and deploy him as a device to turn the districts against Katniss. He’s rescued at the end of Mockingjay: Part 1, but spends Part 2 grappling with his misguided hatred for Katniss and his compulsion to kill her, thanks to the Capitol’s programming.

Heavy stuff for a teen romance. But seriously, while there is a love triangle between Peeta, Katniss and her childhood friend Gale Hawthorne (Liam Hemsworth), who joins her in the fight against the Capitol, the filmmakers are right not to give the romantic storyline more weight than is due.

Katniss comes close to unraveling under the pressures she faces. Her life, and those of her loved ones, is almost constantly in jeopardy. If that weren’t far more than enough, she’s forced to quickly learn hard truths about her world and everyone in it. At a phase when most people take many years to figure things out, adolescent Katniss has to make sense of it all at warp speed, and under life-or-death circumstances. It’s a complex psychological task, and one that would certainly overshadow the pressure to choose a boyfriend.

“I thought it was good that Mockingjay didn’t focus too much on the relationships,” says Isaac. “The movies are about the districts trying to take over the Capitol.”

While the first two films focus on the Hunger Games themselves, Mockingjay’s two-parter is “more about the politics and strategy, more about the rebels’ insurgency against the leading government,” says Jon.

It’s less about the games than it is about refusing to play them anymore. Not that the Capitol’s President Snow (Donald Sutherland) doesn’t try to keep throwing the protagonists into the arena, especially as they hit closer and closer to home.

So, given that the series is called The Hunger Games, do the Mockingjay installments stand alone as films? Or do they require some background reading and viewing?

“They were good, I thought they related well to the book,” says Jon, who is both literary and very literal. “But if you want to see the actual plot of the Hunger Games, I recommend watching the first two movies before seeing Mockingjay.”

“You wouldn’t really get the Hunger Games part if you just saw the two Mockingjay films,” says Isaac. “But they’re still good movies overall, even if you haven’t read the series or seen the first two movies.”

Jon recently started a politics section in his junior high school’s paper. Given his interests, I asked how he thought the films relate to real-world events and what lessons we can glean from them.

“It focused on the rebels against the government in power, so it could reflect a lot of what’s happening in Syria,” he says. “I think that if (something like the Hunger Games) were to happen in the future, that a rebellion would happen faster than (the 75 years it took) in the book and the movie.”

As far as lessons learned, Jon has some very wise words: “The districts themselves should have some power. The power shouldn’t all be with the Capitol.”

Before seeing Mockingjay: Part 2, I’d been wondering how the film adaptation would handle the ending. Mockingjay the book ends with some powerful, poetic words. I knew they wouldn’t cut them. But the words are written in Katniss’ voice, as the narrator, and also I knew the films, which never use narration, wouldn’t resort to it in the last moments of the final installment.

I’ll let you see for yourself how the filmmakers dealt with the challenge. But I did want to see what Jon thought of it. “I liked how they handled the final words,” he says. “It would have been different if they’d done narration. But overall I didn’t like the ending. But I’m the worst person to ask about endings; I, for one, generally hate the endings of all final movies and books in a series because I just hate the fact that they have to end.”

I love that.

As for Isaac, even though the Mockingjay installments don’t deal as much with the actual games as the first two films, the two-parter is still “a good continuation of the series and a good conclusion,” he says.

If The Hunger Games movies do have to end, they do it well. Director Francis Lawrence, who stepped in after the first film, does a solid job bringing Mockingjay to the screen. “The action was pretty good,” says Isaac. “They had good special effects for the booby traps (when the rebels invade the Capitol) and the weapons and stuff like that.”

The Mockingjay films also draw some fantastic performances from the actors. As Katniss, Jennifer Lawrence leads the way; she more than rises to the task of making her complicated character believable—and heart wrenching.

In addition to Hoffman, Moore and Sutherland, standouts from the impressive supporting cast include: Elizabeth Banks as former tribute escort Effie Trinket; Woody Harrelson as past District 12 victor Haymitch Abernathy; Jenna Malone as embittered District 7 victor Johanna Mason; and the always-great Stanley Tucci (Spotlight, The Lovely Bones) as Hunger Games MC Caesar Flickerman.

So that’s that—the Hunger Games franchise, as seen by an aunt and two nephews. Thanks to Jon and Isaac for introducing me to the series and sharing their thoughts (and being so totally awesome).

Spotlight

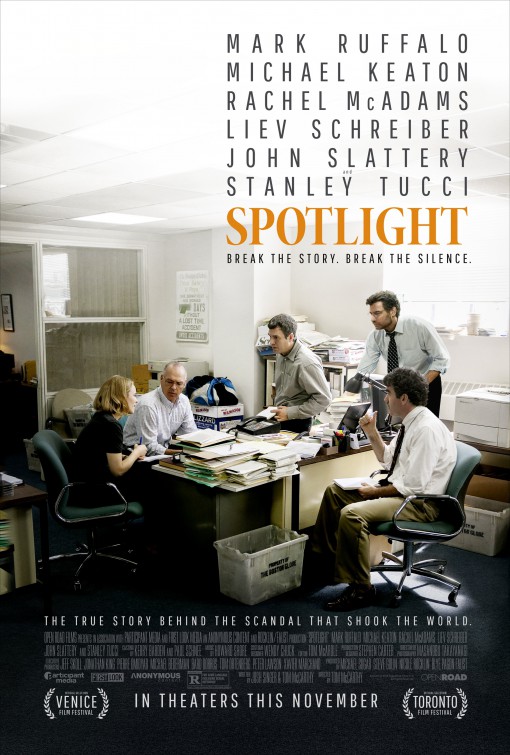

Tuesday, November 17th, 2015—FilmSpotlight (USA 2015, Biography/Drama/History), Writers: Tom McCarthy, Josh Singer; Director: Tom McCarthy

In a 2013 interview on The Colbert Report, British philosopher, humanist and author A.C. Grayling proclaimed that, on the whole, religion has done “far more harm” than good. Grayling was on the show to discuss his book The God Argument: The Case Against Religion and for Humanism.

Tom McCarthy’s new film, Spotlight, makes a similar case. It depicts the 2001 investigation by The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team into the pandemic of child sexual abuse at the hands of the Catholic Church. The journalists’ commitment to wrenching the story out of darkness finally exposed the cover-up that had been quietly documented for decades, and almost certainly going on for much longer.

Spotlight is about the process, the daily grind of bringing such a sweeping story to the foreground. It doesn’t focus on sensationalized reenactments of molestation, or low-angle shots of sinister priests with cheekbones chiseled from shadow. It doesn’t spin the narrative as a thriller because it doesn’t need to. The subject matter is horrifying enough.

Instead, Spotlight hones in on the individual steps each of the reporters must take to pull the story together: late nights at the library; hours squinting through archives in dimly lit basements; interviews and interview attempts; frequent meetings with lawyers; stale hot dogs and leftover pizza dinners.

The film lets us hear some of the survivors’ stories. But even those are seen through distanced eyes, as the reporters target the facts and not the emotions. Because, as the Globe team points out, it isn’t about one particular case of abuse, or even 87; it’s about the system that allowed it to happen.

McCarthy is a perfect choice for covering this subject matter. In his deft hands, watching journalists pore over documents and answer phones isn’t dull; it’s compelling.

He’s already proven his gift for pacing and his light touch with actors, most notably with The Visitor—and Win Win was also a victory. With Spotlight, McCarthy makes full use of his talents, expertly directing an exceptional ensemble cast that more than does justice to their real-life counterparts.

The Spotlight Team includes lead Walter “Robby” Robinson (Michael Keaton, fresh from his incredible turn in Birdman) and his reporters Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James), Mike Rezendes (the always magnetic Mark Ruffalo—see The Kids Are All Right) and Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams, delivering some of her best work yet, in a carefully studied performance that follows a string of progressively more interesting and challenging roles; her artistic integrity makes me keen to feature her on Kickass Canadians).

Spotlight also features fine work from Liev Schreiber as the Globe’s new editor, Marty Baron; John Slattery as deputy managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr.; Billy Crudup as morally questionable attorney Eric MacLeish; and Stanley Tucci as Mitchell Garabedian, the extraordinary lawyer who fought, and continues to fight, on behalf of sexual abuse survivors. Tucci is a high point in every film he graces, but it’s especially nice to see his 2010 portrayal of a child sex offender in The Lovely Bones offset here by a well-drawn portrait of a man looking to correct the crime.

Excluding MacLeish, this dedicated group bands together to challenge an authority so entrenched, almost no one is willing to fight back. Its reach extends far and wide, within Boston and throughout the world, keeping people from speaking out against even the most horrific abuse of the most innocent among us.

Some of the journalists struggle with their own complicity in the scandal; they were all raised Catholic—how could they not have known? But as Garabedian, a man of Armenian descent, points out, “it takes an outsider” to clearly see the situation and be prepared to expose it. Case in point: It wasn’t until Baron, a Jewish newcomer to Boston (or “an unmarried man of the Jewish faith who hates baseball”), came on as Globe editor that the Catholic Church investigation was finally assigned to Robinson’s team.

Spotlight offers a damning, if cool-headed, indictment of religion, its power to corrupt and its potential as a weapon of mass destruction when held in the wrong hands. The film tells this message through incidents that took place nearly 15 years ago (and then some). Yet its message is still urgently relevant today.

* * *

The Spotlight Team won a 2003 Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. Their groundbreaking article, “Church allowed abuse by priest for years,” was published January 6, 2002.

Thanks to Cinemablographer‘s Patrick Mullen for the earlybird tickets to Spotlight. The film opens across Canada on November 20, 2015; I highly recommend it.

If you’d like a chance to see sneak previews of upcoming films, visit Cinemablographer’s contest page. (He’s also got lots of great reviews, so check it out!)

Room

Sunday, November 15th, 2015—FilmRoom (Ireland/Canada 2015, Drama), Writer: Emma Donoghue; Director: Lenny Abrahamson

I haven’t quite left Room yet. I was transfixed throughout the film, and wasn’t able to step completely outside of it after going home; I even spent part of my dreams there.

Room is where Ma (Brie Larson) and her five-year-old son, Jack (Jacob Tremblay), live. It’s a compact space where small moments have huge meaning, and where perception marks the difference between joy and despair.

Ma and Jack are captives of Jack’s biological father, Old Nick (Sean Bridgers), but the boy doesn’t know it. He was born in Room; it’s his whole world and universe—not the shed his young mother was locked into seven years earlier.

Ma does what she can to shelter Jack from the horror of their existence, making up stories and tucking him away in Wardrobe when her captor makes his nightly visits. But when Jack turns five, his growing inquisitiveness and the threat of further interference from Old Nick make it clear they can’t stay in Room forever.

So Ma seizes a rare, and risky, opportunity to escape the tiny space. And in doing so, she hurls herself and Jack into a world neither one is prepared to handle.

What follows is a brilliant mix of beautifully on-point explorations of character and psychology, and dreamlike observations that only seem possible from someone new to the world, from children full of wonder. At times, Jack’s innocent yet deeply insightful reflections reminded me of Beasts of the Southern Wild.

One of Room’s greatest strengths is that it dives straight to the deepest end of what really matters in the story. Forsaking coverage of Old Nick’s capture, it focuses instead on the struggles everyone in Ma’s family faces upon her return—including her now-estranged parents (Joan Allen and William H. Macy), who must each come to terms with what it means to have their daughter back and to have Jack as their grandson.

Room is based on Emma Donoghue’s novel of the same name, and the author also delivered the screenplay. She did a stunning job of translating her original work to the screen.

I haven’t yet read her book (though I look forward to it), but from what I gather, it’s told exclusively from Jack’s perspective and takes place almost entirely within Room’s four walls (and Jack’s imagination, I presume). The film is very much aligned with Jack’s point of view, but it takes us outside his young mind by showing us other characters’ reactions and expressions; we’re able to glean more than he can. Where Room the novel relies on Jack’s voice to form the story’s underlying fabric, the film weaves his narration in and out of the narrative.

I can imagine the power and originality of the book’s approach. But as someone who hasn’t read it, I found the film version to be extremely effective on its own, even if some of Jack’s unique colouring fades in the adaptation. It moves gracefully from being whimsical to gripping and back again, sometimes frequently within the same scene.

The actors deliver exceptional work, including extraordinary naturalism from Tremblay, and an impeccable performance from Larson—controlled, yet utterly raw. She managed to bring weight to a near-silent role in Don Jon; here, her entrancing portrayal of Ma is sure to garner an Academy Award nomination (if not the award itself). Together, Larson and Tremblay create a magical connection, depicting the unbreakable bond between mother and child—one that makes you believe in the power of good over evil.

As wrenching as the subject matter is, the movie makes room to uplift and affirm. It’s a gorgeous piece of filmmaking that veers into darkness, but ultimately proves the resilience of childhood and the human spirit. After all, “we all have the same strong.”

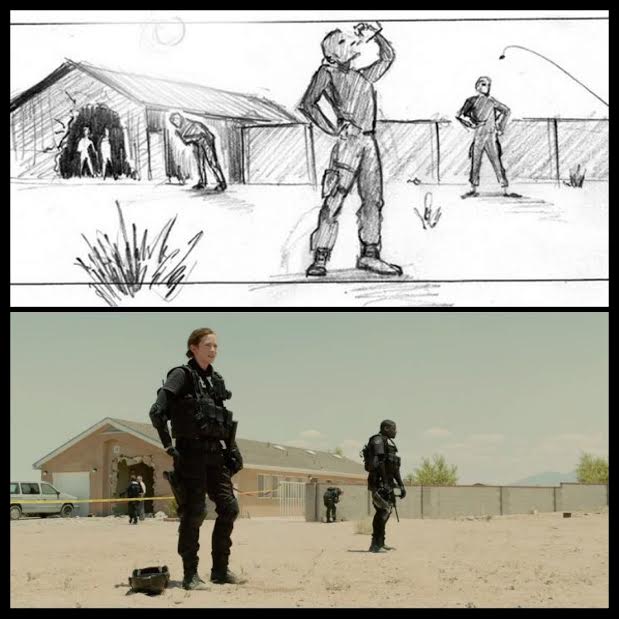

Sicario (feat. storyboard artist Sam Hudecki)

Tuesday, October 6th, 2015—FilmSicario (USA 2015, Action/Crime/Drama), Writer: Taylor Sheridan; Director: Denis Villeneuve

Breathtaking. That’s probably the best word to sum up Sicario, if I had to choose one. The film had me in its grip from beginning to end, closing in tighter with each pulsing beat.

Sicario is about idealistic FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt), who is recruited to join a covert government task force looking to curtail the drug war that rages around the Mexican–U.S. border. It’s also about cultures in crisis, and an increasingly violent world that’s showing signs of growing numb to death and destruction, and that believes more and more that the end justifies the means.

The film begins by explaining the origins of its title: sicarii was the name given to zealots in ancient Jerusalem who fought off the Roman invaders to protect their homeland; in Mexico, sicario means hitman.

That introductory text is the first heavy hit the film delivers—along with its unnerving score. Right away, Sicario makes it clear that it intends to throw open the box full of questions, each of which has no clear answer. Which land is the homeland? How can we truly tell the invaders from the protectors?

The deeper Kate delves into the operation, and the further she dives into Mexico, the more she realizes just how much darkness she’s treading in. Team leader Matt Graver (Josh Brolin) of the U.S. Department of Defense doesn’t even do Kate the courtesy of operating on a “need to know” basis; it’s more of a “deign to let you know” scenario. The cryptic Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), who is also part of the unnamed team, presents an even bigger mystery; he’s a “ghoul” whose origins and intentions remain in the shadows as long as he can keep them there. (Dropped off the edge again down in Juarez…)

With Sicario, director Denis Villeneuve revisits some of the territory he explored in Prisoners: How far should one go in pursuit of justice or revenge? Is it okay to take the law into your own hands if the truth is tangled up in red tape? And when is violence acceptable? Where is the line that separates victim from perpetrator? The questions keep coming.

From what I can tell, to Villeneuve, violence is only acceptable when it exposes the damage done; never when it’s presented as entertainment. In the film’s opening sequence, Kate and her partner, Reggie Wayne (Daniel Kaluuya), lead a deadly raid on a house in Phoenix, Arizona. They’re looking for hostages, but instead they find corpses stacked vertically between the walls—plaster tombstones sealed by bleak paint jobs.

Even after Kate flees the house, standing in its backyard of dust as she and her team reel from the discovery, we’re not safe from what stands inside. Villeneuve takes us back to glimpse ever closer at the faces of those who fell victim to the drug cartels.

The directorial choices that make the opening sequence, and all the rest, so impactful are why Sicario left me breathless. It showcases some of the best filmmaking talents working today, led first and foremost by its profoundly gifted and ruminative director.

Aside from Villeneuve, the person who might be most responsible for the film’s chest-clenching effect is composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, who delivers a stunning score full of cello, percussion and electronics. His music haunts the movie, snaking and rattling through scenes as it makes its way from simmering to seething.

Lighting master Roger Deakins pulls off extraordinary feats of cinematography, particularly in low-light settings (including one incredible sequence in a tunnel, shot using night vision and thermal-image cameras). Taylor Sheridan’s script is brilliant (amazingly, Sicario is his debut screenplay). In the lead roles, Blunt, Del Toro and Brolin are excellent, each as skilled as they are talented. Editor Joe Walker pulls it all together, making for taut, tightly wound coil of film that threatens to snap off the spool at nearly every frame.

Those are some of the headline names associated with Sicario. But as with any film of this scale, there are of course many more artists who played a critical hand in making it happen. One of those people is storyboard artist (and Kickass Canadian) Sam Hudecki.

Sicario is Sam’s third collaboration with Villeneuve, after Enemy and Prisoners (and before next year’s Story of Your Life and their current collaboration, the Blade Runner sequel). I worked with Sam many years ago, after we graduated from Queen’s University’s film program, when he was 1st assistant camera on my short movie Sight Lines. He’s now in the midst of a pretty thrilling project, but he graciously made time to chat with me for this review and share his behind-the-scenes insights.

Sam spent three months in pre-production on Sicario, working alongside Villeneuve in New Mexico. “I really love working with him,” says Sam. “I think we established a great working relationship, and (storyboarding with him is) my favourite creative process to be in.”

It’s a process that always begins with a conversation. Going back to Sicario’s opening sequence, Sam says there was a lot to talk on that front. “Denis and I had many conversations about the nature of violence. Do you show a grenade before it goes off, or do you witness an explosion and the suddenness of that explosion? (The way we approached violence in the film) was a decision that came out of a lot of discussion around the potential impact of that opening sequence.”

There’s another sequence in the film that stands out to me, one that’s equally impactful. After the special ops team travels to Juarez to capture one of the top players in the Mexican cartel, they bring him back for “questioning” at the hands of Alejandro. Alejandro sidles down the hall and into the interrogation room, whistling all the while, toting a jug of water. When he approaches the captive, Alejandro doesn’t strike him; instead, he saunters up so close to him that the looming attack starts to feel almost intimate. It’s one of the most intimidating moments I’ve seen in a film.

Mercifully for the viewer, if not the captive, the violence takes place off-screen. We don’t need to witness it; Alejandro’s quiet menace bares all.

From everything I have seen, Villeneuve displays that sensitivity toward violence in all his films. He also shows great empathy toward women. I touched on that in my Prisoners review; to me, it’s a trademark of the director’s approach, and one I value very highly. (For more on this, see my Kickass Canadians article on Villeneuve.)

He does it again with Sicario, which strongly emphasizes Kate’s point of view in a male-dominated world. So it’s somewhat shocking (from an artistic perspective, if not a business one) to learn that backers who initially looked at the film wanted Kate replaced with a male protagonist. To make the lead character a man would completely change the story. It would be to lose Kate’s inherent vulnerability, the eyes through which we see the story—those of an outsider.

Fortunately, with Villeneuve involved, there was no need. According to Sam, “Denis brought a lot of attention and sensitivity” to Kate, something Sam himself appreciated.

“I love the fact that the protagonist is a woman,” says Sam. “She’s in a position that would be tough for anyone, but it’s particularly tough for Kate because she’s a woman on a (dangerous, questionable) mission led by men, and she has strong ideals. So her point of view was certainly something we were very acutely aware of in our approach. As (the team goes) into Mexico, we’re very aligned with Kate.”

Adopting an outsider’s perspective was a key factor for Sicario, given that the crew couldn’t film in Juarez, where many key scenes were set. We see it only from a distance, which is fitting given that our impressions of the city are framed by someone who doesn’t truly understand what she’s being drawn into. “You only get to know a hint of what’s really going on there, and that’s as far as we could take it,” says Sam.

Shooting in Mexico, if not Juarez itself, was important to the filmmakers because they very much wanted to create an authentic depiction of the area. “We looked a lot at what is really going on,” says Sam. “And while there’s artistic licence, (the film) comes from a place of being very grounded in reality.”

Still, Sam stresses that Sicario isn’t intended as “an advisory of any kind about Juarez. It’s more of a meditation about conflict (in general).”

The subject matter isn’t surprising when you consider the source; Villeneuve has become known for his penchant for exploring the darker side of humanity. But that doesn’t mean the director himself is mired in gloom.

“I read somewhere that people (assume) he must be a very dark and depressed person,” says Sam. “It’s not true; it’s actually quite hilarious and tremendously enjoyable to work with him.

“The purpose of storyboarding is just to get everyone on the same page, and that page is Denis’ vision—his dream of the film. My job is to help unlock the dream and get some of that on paper. So it’s always kind of a first blush, and I know that when Denis and I can look at each other and think, ‘This is exciting,’ I know that it will be.”

I’m still catching my breath.

* * *

Thank you, Sam, for sharing your time and thoughts with me. Here’s a shot of us and the Sight Lines cast and crew, on set in 2002 (Sam’s left of the camera; I’m to its right, in jeans):

Keep an eye out for the next two collaborations from Sam and Villeneuve, two of Canada’s greatest film talents—Arrival, set to release in early 2016, and the Blade Runner sequel, scheduled to start shooting in summer 2016.

* * *

From Tori Amos’ ‘Juarez’:

Dropped off the edge again down in Juarez |“Don’t even bat an eye | if the eagle cries,” the Rasta man says, just cause the desert likes | young girls flesh and | no angel came.

Mad Max: Fury Road

Monday, June 1st, 2015—FilmMad Max: Fury Road (USA 2015, Action/Adventure/Sci-Fi), Writers: George Miller, Brendan McCarthy, Nico Lathouris; Director: George Miller

I can attest that you don’t have to know anything about the original Mad Max movies to appreciate writer/director George Miller’s latest entry to the franchise, Mad Max: Fury Road.

The 2015 installment features Tom Hardy in the role Mel Gibson made famous in the late 70s and early 80s. I don’t know what Gibson’s portrayal was like, but in this round, Max Rockastansky is a damaged yet fierce warrior who is incapable of giving up. As he says, he’s been reduced to a single instinct: survive.

Mad Max: Fury Road is set 45 years after the world falls apart. So we don’t know exactly what year it takes place, but we can pray that it’s much, much later than 2060.

The world in which Max exists—barely—is a fiery desert (he calls it a wasteland of fire and blood), where he is “hunted by scavengers and haunted by those I could not protect.” I keep quoting the script because it’s surprisingly poetic; it really sticks with you.

In the opening sequence, Max is captured by the greedy scavengers, in spite of a ferocious and amazing attempt to escape. Chained and strung upside down, he’s used as a “blood bag” (just imagine) for the warlords who serve Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne, who played Toecutter in the first Mad Max movie).

Immortan Joe is an aged dictator who keeps women prisoner so they can bear his children, or pump “mother’s milk” for his adult sons to guzzle. He starves the masses living below his kingdom, the Citadel—although he’s good enough to take time out to warn them of the perils of becoming addicted to water.

It’s a hellish world, and therefore an unsustainable one. Many are angry, and many more are dangerously unhappy.

One of the angriest is Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron). When she steals Immortan Joe’s most prized possessions (his wives, or “breeders”) in the hope of setting them free, a feverish chase ensues—one that gets Max out of the shackles. And one that lasts nearly the full two hours of the movie.

Now, I like action, but only if it’s well done and not if it goes on too long. At some point fairly early in the film, I realized that the entire thing was going to be a prolonged chase scene. I was worried for a minute, but Fury Road pulls it off. Yes, I wouldn’t have minded a few more quiet conversations between characters, or more of a reprieve. But this film is so exceptionally made that it absolutely won me over, even as someone who doesn’t love uber-long action sequences.

Miller is as much a dedicated perfectionist as he is a brilliant visionary. The effort and talent that went into making Fury Road is simply astonishing. The patience and perseverance, the stamina it would take to spend seven months in the Namib Desert, giving everything to each shot, each take, maintaining the creative energy required to deliver such an explosive and innovative final product… It kind of blows my mind to think of it.

Pick any aspect of the film to focus on and you’ll see how exceptional it is. Great genre story that creates characters and settings so established, they feel almost legendary. (Names like Toast the Knowing, and Cheedo the Fragile, are assigned with such authority; while watching, I wondered whether Fury Road was based on a series of graphic novels.) Amazing effects and stunts, inventive props and costumes, meticulous direction, stunning editing, excellent cinematography. The sound! The frenetic, pounding score by Junkie XL!

The acting. So many impressive performances. Sticking to the main three: Hardy fits the image of the classic action hero, but he brings much more than muscle to Max. Here’s a man with a great gift at conveying his depth and soul, even when barely speaking. Theron, who has to be one of our best living actors, nails it every time (see The Road); Fury Road is no exception. Nicholas Hoult, as young warlord Nux, delivers a layered and complex portrayal, treating his seemingly sleazy character with compassion, rounding him out with powerful subtext and heaps of personality.

It’s amazing how much depth the actors convey, given the sparse script they worked from. Fury Road relies on expressions, gazes and body language to capture much of its story, its pulse. Even in intimate moments between characters, the film is still more about action than dialogue.

That’s a big part of why Fury Road works. Though it may be one prolonged chase scene, it has a solid heart at its core—one that keeps you caring even if you’re far past your “action sequence” threshold (if you have one). Oh, and the action itself is spectacular.

Hats off to the filmmakers—cast and crew alike. What an achievement.

Fury Road’s follow-up, Mad Max: The Wasteland, was recently announced, with Hardy resuming the title role. I’m in.

* * *

The Fury Road panel discussion at the Cannes Film Festival offers some great insights, from the film’s cast, as well as from Miller, his producing partner, Doug Mitchell, and his editor (and wife), Margaret Sixel. Worth a watch.