Archive for the ‘Film’ Category

« Older EntriesNewer Entries »

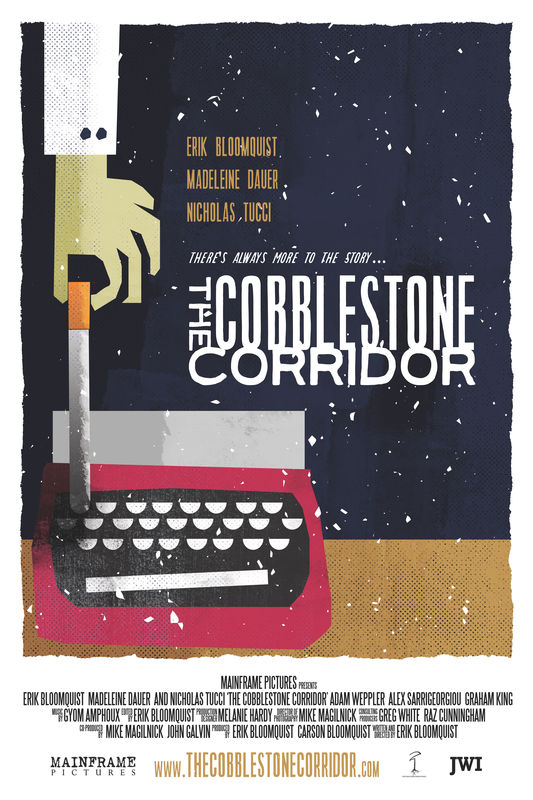

The Cobblestone Corridor

Friday, May 22nd, 2015—FilmThe Cobblestone Corridor (USA 2015, Short/Crime/Mystery), Writer/Director: Erik C. Bloomquist

For various reasons, I’ve neglected this blog lately (one reason is my other website, Kickass Canadians). But I’m thrilled to return to it for The Cobblestone Corridor.

When writer/director Erik C. Bloomquist asked me to review his latest short film, it reminded me of the direction I want to steer this blog towards: interviewing filmmakers (Winter’s Tale, Northword, Take This Waltz and Barney’s Version), taking requests from indie directors to help promote their work (Wanderweg), and doing joint reviews with pals—and of course my amazing nephews (The Lego Movie, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Outland).

So here are my thoughts on The Cobblestone Corridor: I’m very impressed.

The 25-minute movie is a tribute to film noir and old-school detective flicks. It tracks Allan Archer (Bloomquist), editor-in-chief for the newspaper at Alfred Pierce Preparatory School, in hot pursuit of his biggest case yet: investigating the dubious dismissal of Dr. Peter Carroll, chairman of the English department.

Mannerisms and catchphrases aside (gumshoe, dame), The Cobblestone Corridor’s world is very much rooted in modern-day America. In the realm of prep school newspaper nerds (self-described!), that means going head-to-head with a public that prefers insta-news and chat rooms to well researched articles and educated commentary. The film takes pains to argue in favour of traditional journalism (although the Internet ultimately proves handy in solving a certain case…). It’s an interesting exploration, one that is particularly at home in a film that so lovingly embraces the traditions and past conventions of another form of media—cinema.

The Cobblestone Corridor has its tongue firmly planted against its cheek. Case in point, Allan’s deadpan response to a suspect who calls him four eyes: “I wear contacts now.” (The nerd of noir may have ditched his glasses, but he’s still looking through a similar lens.) Yet what brings the film home is how fully the characters, and actors, commit. They’re utterly earnest about the plot twists and developments, and the result is a charming, absorbing 25 minutes of classically contemporary storytelling.

The Cobblestone Corridor is a slick movie, with great cinematography and production design, and solid performances across the board. Kudos to the entire team.

Bloomquist in particular makes a strong impression, doing quadruple duty as writer, producer, director and star. He’s also clearly committed to getting the word out about his film; this blog can’t have a very high profile, yet he came across my Canadian site while reaching out to bloggers to promote his American film. Dedicated, hard working and talented—seems safe to say Bloomquist is going places. Visit his website to learn more.

The Cobblestone Corridor is available to rent or buy through Vimeo on Demand. The price is low, the quality high. I hope you’ll check it out.

Thanks to Erik for sending me the press kit and inviting me to comment on his work. He has inspired me, renewed my excitement for indie filmmaking, and reminded me of the power of believing in your ideas and seeing them through.

A Most Violent Year

Thursday, February 5th, 2015—FilmA Most Violent Year (USA 2014, Action/Crime/Drama), Writer/Director: J.C. Chandor

A Most Violent Year is a tightly packed nutshell of mood and American ideology that creates a palpable tension from beginning to end. It’s as if the thing might crack open at any moment, spewing forth the violence it alludes to (but rarely shows) and releasing the microcosm of America it contains, allowing its dream-woven seed to take root.

The year is 1981, historically one of New York City’s most violent years. Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac) is a hardworking and ambitious immigrant who owns a heating oil business. He’s poised to close the biggest deal yet of his career, but his success is threatened by attacks against his salespeople and a growing number of violent robberies that send his drivers to the hospital.

As his last name suggests, Abel is committed to doing the right thing (or at least “the most right thing” to achieve one’s goals). But his wife, Anna (Jessica Chastain), who is a gangster’s daughter, has other ideas about how to get things done: “You’re not going to like what’ll happen once I get involved.”

References to The Godfather abound, as well as to Macbeth; Chastain channels Lady Macbeth in much the same way Marcia Gay Harden does in Mystic River.

The American Dream also features prominently, with two opposing experiences playing out through Abel and his driver Julian (Elyes Gabel), who doesn’t fair nearly as well in a world of violence, greed, ambition and corruption. Ultimately, it seems that success comes down to who cowers in the face of fear and who chases it into the ground. (In Abel’s words, “When it feels scary to jump, that is exactly when you jump. Otherwise you end up staying in the same place your whole life. And that, I can’t do.”)

A Most Violent Year is a captivating film. It’s a slow-going train (as Blaine Allan, one of my Queen’s University film profs, would say, “it moves at a measured pace”), but nothing is extraneous. Every stop along the way, from the dialogue to, for example, Abel’s running sequences, reveals something important about the plot or the characters. Much like Abel’s approach to business, the film is efficient and well oiled.

It also does a marvelous job of creating mood, thanks in no small part to Bradford Young’s dark, beautiful cinematography and Alex Ebert’s haunting score. And it features wonderful performances across the board, most notably from its leads. As Abel, Isaac is so very different from his role in Inside Llewyn Davis, but every bit as good. Chastain also continues to display her staggering versatility (see The Tree of Life, Take Shelter and Zero Dark Thirty).

A Most Violent Year closes with an impactful ending that comes as something of a surprise—a final stop after you thought the ride was over, and one that brings Abel’s character into sharper focus than ever before.

A most impressive film. I’ll be on the lookout for whatever comes next from its writer/director, J.C. Chandor, and from the always excellent Isaac and Chastain.

Nightcrawler

Sunday, November 2nd, 2014—FilmNightcrawler (USA 2014, Crime/Drama/Thriller), Writer/Director: Dan Gilroy

Just in time for Halloween, Nightcrawler brings us the ghoulish Lou Bloom, a thief-turned-snuff-filmmaker (okay, technically, turned freelance videographer who captures overnight carnage for the morning news) whose creepy exterior hides an even scarier inner demon. This haunted creature is all about the tricks; fortunately, the film itself is a skillfully made, thought-provoking treat—as long as you like hard candy.

When Nightcrawler opens, Lou (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a petty thief skulking around Los Angeles after hours, snipping chain link fences and scrounging for valuable trinkets. But when he stumbles on a bloody car crash and sees videographers (or “stringers”) snapping up the footage, he discovers his true calling.

Lou sells his footage to Nina Romina (Rene Russo), the news director at a struggling TV station, whose vulnerable tenure makes her an ideal target for Lou’s exploits and exploitations. Before long, he climbs the slippery ladder of success—never mind if he has to crush a few fingers (or throats) along the way; in fact, so much better.

Whether he’s slinking past police DO NOT CROSS barriers or breaking moral boundaries, Lou quickly proves there really is no line he won’t cross. And it works; with hard work, ruthless dedication and a little bloodlust, anyone can make it in today’s world. Welcome to the American Nightmare.

Nightcrawler offers its own grisly exposé on a number of news items, all with its particular brand of dark, satirical humour. There’s the shaky economy, in which unpaid interns and underpaid workers abound, not to mention the criminals who hire them. Lou fast-talks derelict Rick (Riz Ahmed) into becoming his assistant for a meager $30 per night—a “raise” that brings a smile of relief to the poor man’s face. Nightcrawler also preys on our collective taste for the sensational and our obsession with the media. The more graphic Lou’s footage gets, the higher Nina’s ratings soar; as they say, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

The film portrays a world in darkness. I mean that literally; most of Nightcrawler takes place at night, when creatures like Lou slink out of hiding to go on the prowl. But more than that, the film depicts a world in which nearly everyone is susceptible to corruption, and where life is so grim that people look to escape from the growing darkness in any way they can. Even if it means watching news segments that brutally depict human tragedy, and human depravity, in gross detail.

In Nightcrawler’s world, no one is more depraved than Lou himself. Yet he has crafted his identity from the influences of the world at large—from the rest of us. A sociopath looking to fill his emptiness, he gleans his identity from the Internet. He admits he never had much of a formal education, but believes “you can find most anything if you look hard enough.” So he’s an autodidact, with the Web is his primary thesis advisor.

In many an aggressive monologue, Lou doles out catchphrases and motivational jargon, dredging up pat philosophies and self-help mantras to justify just about all his actions. But for all his talk, he can’t conceal the hollowness at his core.

Lou speaks volumes when he delivers the film’s opening line: “I’m lost.” He’s gone off course, and so has the world he’s trying to manipulate.

More than lost, Lou is also hungry. I heard an interview in which Gyllenhaal describes his character as a coyote: vicious and predatory, in search of his next meal. You can see Gyllenhaal’s artistic choice in his performance; in the way Lou sidles up to others inappropriately, gauging their reactions, getting as close as he can, unperturbed when they try to shoo him off. Okay, so Lou Bloom’s embodiment of a coyote is more than a little deranged, maybe even rabid. But you get the idea; he’s a creature of the night, and he’s out for the kill.

It’s a transformative performance from Gyllenhaal, who seems intent on pushing the boundaries of his art and craft (see Enemy, Prisoners and If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet). With Nightcrawler, he’s definitely reached another level in an already impressive career. His misanthropic, psychopathic Lou is as convincing as he is horrifying.

Gyllenhaal is backed by stellar performances from the entire cast, including a pitch-perfect Russo who eerily steers Nina over a rather disturbing character arc, as well as an outstanding Ahmed, and a compelling Bill Paxton as competing videographer Joe Loder. But there’s no question that Nightcrawler belongs to Gyllenhaal—and of course to writer/director Dan Gilroy, who envisioned it all and who makes a staggering directorial debut, after penning flicks such as Real Steel and The Bourne Legacy.

Kudos to all on a great film, and thanks for the thrills and chills; I couldn’t have asked for a better Halloween treat.

* * *

Thanks also to GC and NC for the company and the candy!

Gone Girl

Thursday, October 16th, 2014—FilmGone Girl (USA 2014, Drama/Mystery/Thriller), Writer: Gillian Flynn; Director: David Fincher

[Spoiler Alert: I touch on some of the film’s pivotal plot points, although I keep the ending itself a bit vague. Unless you’ve read the book, you may want to see Gone Girl before reading this entry. If not, consider yourself warned.]

I haven’t read Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, the book on which David Fincher’s latest film is based. From what I gather, the book contains many of the elements I found lacking in the movie, so maybe it would be best if I read the novel before writing this review. But I’m not sure when I’ll get to it, and given that it’s been nearly four months since my last confession—just kidding, my last blog entry—I’m going for it.

In the film, Gone Girl examines what happens when Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) goes missing on her fifth wedding anniversary to Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), and fingers start pointing at her husband.

I’ll just come out with it: I didn’t love the movie as much as most people seem to. That’s not to say there isn’t a lot to admire about Gone Girl. It’s skillfully shot, and features a buffet of solid performances, including one of Affleck’s strongest, and another stellar turn from Pike, who always impresses (see Barney’s Version). Fincher has a particular gift for drawing out greatness from his actors.

The director also has the smarts to keep collaborating with artists who can deliver. Fincher brings his The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo composers, Trent Reznor and Attitus Ross, back to score Gone Girl, adding an extra layer of creepiness. (I’m playing the soundtrack while writing this and it’s really affecting my mood.)

Technically and artistically, Gone Girl gets a lot right. My issues with the film have more to do with the story itself and the messages it presents.

From the opening shot of the back of Amy’s head (which plays out as Nick explains in voiceover that he often thinks of cracking open her skull to see what really goes on in her mind) and the film’s abrupt conclusion, you get the impression that Gone Girl purports to explore how marriage, or merely coupledom, perverts us as people, makes us put on masks and pretend to be something other than what we truly are—or even want to be. But much of the rest of the film undermines that notion, treading instead into murky and even dangerous waters that have a sexist undertow, and that made me more than a little uncomfortable.

[Again, SPOILER ALERT!]

As Nick and the police piece together what could have happened to Amy, we learn that she staged her abduction, and presumed murder, to frame her husband as a means of revenge for his cheating (and generally ruining her life, as she sees it).

In some ways, Gone Girl appears to explore the way women are trapped into fulfilling ideas of who they’re supposed to become, for their partners, their parents, and society at large. There is a strong case to be made there, but in this case, I’m not buying it.

If we’re going to have a strong female character who bucks the trend and wants to take over the reins on a system that tries to manipulate her, why does she have to be a homicidal lunatic with antisocial personality disorder? It would be nice to see that strong woman as someone who can’t so easily be discredited.

It’s interesting that Flynn adapted her own novel for the screen, given the film’s departures. I’d like to know what direction she was given on which parts to remove for the script, and why efforts were made to align the audience’s sympathies more with Nick than with Amy. My elder sister, who read the book and saw the movie, says the novel portrays both Nick and Amy as sociopathic, rather than casting Nick as the victim, and creates a more believable scenario in which they could stay together as a couple. For me, that plausibility is sorely lacking in the film.

As it becomes clear that Amy staged her abduction, is also comes to light that this isn’t her first time up to bat. She has a history of manipulating and framing men, including fabricating a rape to set up an ex-boyfriend. So, she certainly isn’t above contriving domestic abuse at Nick’s hand, via false diary entries left for police to discover (all part of a wedding anniversary treasure hunt, an ode to marital romps gone awry; it’s all fun and games until someone stages a kidnapping and murder).

Amy’s actions are among the ugliest a woman can commit; they discredit the many women who legitimately claim abuse, and malign men who aren’t guilty—at least not of the vile crimes she accuses them.

Last year’s excellent Danish film The Hunt offers a far more sensitive exploration of a man falsely accused, and takes pains to look at why those accusations might come about without any real malice. Then again, that film examines very different sociological phenomena than Fincher’s thriller.

In Gone Girl, it seems as if we’re meant to follow along as the filmmakers investigate gender roles, as well as the very fabric of marriage itself. But their investigation lacks substance, and the emphasis on Amy’s “evil,” for lack of a better word, doesn’t help the cause.

There are fleeting examples of Nick’s father being a misogynist, but his role feels like an underdeveloped holdover from the novel. Nick’s mother has passed away, so we don’t get to see his parents’ dynamic. Maybe Nick’s father’s behaviour is meant to imply that history repeats itself in Nick and Amy—and that Nick will go on to become his father—but the film has too many other storylines to pursue, and that one falls by the wayside.

Amy’s parents factor in more prominently. Their hugely successful book series, Amazing Amy, is based on Amy herself, hijacking her life for profit (not to mention passive-aggressively shaming her for not living up to expectations). Her parents “improve upon” her milestones; real-life Amy quits the violin, so fictional Amy sticks with the instrument and turns out to be a prodigy. Perhaps worst of all, fictional Amy walks down the aisle in Amazing Amy and the Big Day, while regular ol’ Amy remains unmarried into her 30s.

That kind of family dysfunction goes a long way toward explaining adult Amy, and I would have liked to see it better dissected. (There isn’t time, though; Gone Girl is already too long and crams in too much.) But it seems clear that it’s Amy’s parents, not her husband, who set her down the path of striving for impossible standards, constantly wrestling with the knowledge that she can never be good enough.

Again, this might also be a case of history doomed to repeat itself, but the impact of Amy’s parents’ marriage and how it distorted their child, as opposed to their parenting itself, isn’t properly examined. I suspect this is better explored in the book, but for now, I can only go by the film, and it doesn’t make a clear case for her parents’ marriage as a culprit in Amy’s dark ways.

What is clear is that Nick and Amy’s marriage never stood a chance. Aside from Amy’s falsified account of Nick’s abuse, his only real affront against her is being unfaithful. He comes across as a good-enough guy who hit rock bottom when he and Amy lost their jobs, and didn’t adjust well when they had to relocate to the burbs when his mother got ill. (The only exception is a brief moment of violence at the end of the movie, but that comes as a result of Amy’s heinous manipulations and murderous ways, so can’t be used to justify her behaviour.)

Amy, on the other hand, distorts the truth and deliberately misrepresents herself from the beginning. She acknowledges that she played the role of “Cool Girl”—a woman who waxes her nether regions and “eats cold pizza while remaining a size 2”—because she knew right away that was the kind of girl Nick wanted. Yes, that is one of the roles imposed on women in our culture, but here, Amy uses it to her advantage, manipulating Nick to get what she wants and dooming their relationship by rooting it in falsity. Becoming “Cool Girl” was her deception; it hardly seems fair to blame that on men or marriage, particularly when she never gave Nick the opportunity to know the “real” her (if Amy even knows who that is).

Speaking of prescribed roles for women, it’s telling that Nick’s affair is with his barely-legal student Andie, who fits perfectly into the “busty and libidinous co-ed” category. Adding even more pack to the punch (or insult to injury?), Andie is played by Emily Ratajkowski, who starred in Robin Thicke’s frightening and asinine display of sexism and ignorance, otherwise known as Blurred Lines (see my Don Jon review for more on this). I don’t know if her casting was a deliberate reference to the objectification of women, but regardless, it’s hard not to reflect on that, given the context.

So, Andie is played by Ratajkowski, Nick is played by Amy, Amy is (eventually and briefly) played by Nick, the public is played by the media; in Gone Girl, everyone gets played. But Amy clearly emerges as the winner, and I think that’s a problem. With the Dunnes—with men and women—positioned as rivals rather than partners, there’s no room for equality or respect. It’s a dangerous game, and not one I want to play.

If Gone Girl is meant to explore and expose gender issues and societal expectations, it needs to present a more balanced scenario—one that doesn’t victimize Nick or vilify Amy. The film starts with a fascinating premise, and maybe the book does a better job of exploring it. But as the movie shows it, there’s too much emphasis on the thriller side of the narrative, and not enough insightful reflection on marriage, gender roles, and how both men and women perpetuate stereotypes. Instead, Gone Girl presents a problematic dynamic between a man and a woman; or really, between Amy and anyone unfortunate enough to cross her path.

It isn’t even that I didn’t like the film. It’s that its depiction of Amy is so disturbing and potentially harmful, and that it wastes an opportunity to present a more balanced and perceptive exploration of gender expectations and relationships.

Gone Girl was produced by Reese Witherspoon’s company Pacific Standard, which is also behind the upcoming Wild, another adaptation of a woman’s novel, though this time autobiographical (and one I’m really looking forward to seeing, at Cinemablographer’s wholehearted endorsement). I saw a clip of Witherspoon endorsing the two films and saying that she plans to continue depicting such strong female characters. Let’s hope that in the future, they’re less vindictive, sadistic and manipulative than Amy.

* * *

In tribute to the greatness of Reznor and Ross’ soundtrack, a couple other musical references…

It was Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Brilliant Disguise’ that ultimately prompted me to write a review of Gone Girl:

I want to read your mind

To know just what I’ve got in this new thing I’ve found

So tell me what I see

When I look in your eyes

Is that you baby

Or just a brilliant disguise

I want to know if it’s you I don’t trust

’Cause I damn sure don’t trust myself

Now you play the loving woman

I’ll play the faithful man

But just don’t look too close

Into the palm of my hand

We stood at the altar

The gypsy swore our future was bright

But come the wee wee hours

Well maybe baby the gypsy lied

So when you look at me

You better look hard and look twice

Is that me baby

Or just a brilliant disguise

And another reference, regarding women who turn conventions on their heads: Tori Amos’ album Strange Little Girls, covering and repurposing a series of songs written by men. Here’s her take on I’m Not In Love by 10cc.

Finding Vivian Maier & Only Lovers Left Alive

Saturday, June 21st, 2014—FilmFinding Vivian Maier (USA 2014, Documentary), Writer/Directors: John Maloof, Charlie Siskel

Only Lovers Left Alive (UK/Germany/Greece 2013, Drama/Horror/Romance), Writer/Director: Jim Jarmusch

I wasn’t planning to write a joint review of Finding Vivian Maier and Only Lovers Left Alive. But I saw them both in the last few weeks (at the marvellous Mayfair Theatre), and when I got to thinking I should write about one, the parallels between the two started seeping through. So here we are.

Finding Vivian Maier is a documentary about the late Vivian Maier, who was a nanny and, as it turns out, a deeply gifted street photographer. Much like many great artists, her work wasn’t appreciated until after her death in 2007, by which time historian John Maloof had stumbled upon some of her many film negatives at a Chicago auction and promptly set about trying to uncover her genius, not to mention her secrets. The final tally for Maier’s negatives is 100,000+, most of which she herself never printed. Maloof’s documentary is an exploration of “the mystery woman” behind the images she coveted and shot, but rarely shared with anyone else.

There’s a lot to observe and ponder in Finding Vivian Maier, but what had the most lasting impact for me was the idea that we never really know who’s walking among us. We can only guess at the stories of each person we pass, on any given day, and most of the time we don’t bother to try—even when it comes to people we interact with regularly.

Maier was definitely among the hidden gems that slipped unnoticed through the cracks (albeit a little rough and cloudy). Thanks to Finding Vivian Maier, we get a few snapshots of her story, a fascinating tale that was likely very lonely, maybe even brutal at times. But we never quite get a full glimpse behind the curtain, largely because of how reclusive Maier was.

It was this example of someone not wanting to be exposed, this idea of people who remain largely unknown to those around them, that prompted me to pair Finding Vivian Maier with Only Lovers Left Alive. This isn’t to equate Vivian Maier with vampires—not at all. It’s just that both films present interesting characters who hide themselves in plain sight, walking among us without ever betraying who (or what) they really are. And who thrive, even survive, off capturing people’s essence—their spirit, their blood—without their consent and usually without even their knowledge.

In Only Lovers Left Alive, vampires tend to feast off blood acquired in bottles from doctors. No one is bitten or killed, and the unwitting donors need not know it ever happened. It’s a highly civilized approach in a world where culture and civility are going down the drain, much to the protagonist’s despair. Adam (Tom Hiddleston), a centuries’ old vampire, is in a deep depression over rampant “zombie-ism”—his word for the current state of humanity, wherein people wander about thoughtlessly, mistreating the world around them, “contaminating their own blood, let alone their water.”

Adam is married to Eve (Tilda Swinton), who is also a vampire, although you wouldn’t necessarily know this about the couple, from the outset. Both Adam and Eve are awfully pale and seem to shun daylight, but it’s awhile before they start guzzling blood and baring fangs. He lives in Detroit, she in Tangiers, and they never explain why (delightfully avoiding exposition). But one can imagine that if marriage lasted centuries rather than decades, it might be nice to have a little room to roam now and then.

The story gets going, as much as it ever does, when Eve travels to Detroit to visit her morose husband (via two night flights, of course). It gets another bite of energy when Eve’s troublesome sister, Ava (Mia Wasikowska), shows up and interrupts the lovebirds’ relatively happy reunion.

It has to be said: Only Lovers Left Alive runs a little thin on plot. But writer/director Jim Jarmusch manages to thicken it anyway with intricate set design, a heady soundtrack and impeccable performances, capturing the sense of eternity Adam and Eve dwell in, without making it boring to watch. His film oozes atmosphere and artfulness; its power is largely in the telling, and Jarmusch tells it very beautifully.

Adam and Eve present the most believable 21st Century vampires I can think of. Deeply immersed in culture, they revel in art, basking in music and literature, coveting antique instruments and mastering multiple languages. They carry the massive sense of history, and perspective on human (mis)behaviour, that any being would, had it lived as long as these two.

I’ll admit the film’s ending is a bit bleak; without giving it away, I found it hard not to interpret the final moments as a relinquishment of hope and faith. (Let’s call the film “Good ‘til the last bite.”) But Only Lovers Left Alive is also full of humorous reflections and clever cultural references, including a fun running joke about Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt).

The uber-culturalism in Only Lovers Left Alive brings me back to my comparison with Finding Vivian Maier. Both films are devoted to art, raising it above all else. Adam and Eve seem to exist for art as much as for each other. (As my pal MF says, art is the only currency they value.) With Finding Vivian Maier, I sometimes got the same sense, from the filmmakers as well as their subject.

Maloof, who frequently appears in the documentary as a talking head, proceeds with his film even though many of the featured interviewees express their doubt as to whether Maier would have wanted to be exposed so publicly. That did make me question whether it was right to produce the documentary. But Maier may well have understood the passion to pursue one’s art at any cost. She was an obsessive photographer who took candids all the time, even when the subjects didn’t seem to appreciate being photographed, and even if it meant neglecting the children she was paid to care for. One interviewee recounts the time a former charge had a fairly serious accident in front of Maier, and instead of helping, Maier stood by and snapped photos.

Finding Vivian Maier gets even darker than that. The film touches on allegations that Maier physically abused some of the children she looked after. True, it also presents statements from former charges who appear to have cared for Maier very much, even into their adulthood, and suggests that she herself must have been “traumatized” in childhood. But none of that excuses child abuse, and I was disturbed by how easily the filmmakers moved away from the allegations.

In many ways, Finding Vivian Maier serves to introduce a selection of possible stories, without fully delving into any: the concept of art and what qualifies as such; childhood trauma and abuse; mental illness; and who Vivian Maier really was. But perhaps that’s as it should be.

One of the interviewees, a shopkeeper whose store Maier frequented, remarks that the story of the photographer and her desire to keep her photographs secret is much more fascinating than the photos themselves (as impressive as they are). I agree, and in some ways, the film’s unanswered questions about Maier are a bit frustrating. But given her desire for secrecy, it’s probably best that so much is left unsaid.

And in the end, the film does manage to provide an insightful glimpse into an intriguing life that was nearly overlooked—not to mention an incredible art collection. For that reason alone, Finding Vivian Maier is more than worthwhile. As Only Lovers Left Alive makes clear, art is invaluable and utterly deserving of our appreciation. After all, it easily outlasts each of us.

* * *

Thanks to TS for recommending Finding Vivian Maier (yet another interesting film!). For more on Vivian Maier, visit VivianMaier.com. Incidentally, there’s another documentary on the artist, BBC’s The Vivian Maier Mystery.

And here’s another review of Only Lovers Left Alive, by my pal Patrick Mullen over at Cinemablographer.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

Tuesday, April 1st, 2014—FilmThe Grand Budapest Hotel (USA/Germany 2014, Comedy/Drama), Writer/Director: Wes Anderson

I don’t know what it is about Wes Anderson movies, but looking back at my Moonrise Kingdom review, it seems I felt the same way I do now about The Grand Budapest Hotel: I loved the movie, so much so that I wanted to get something up on this blog, no matter how short, but I simply didn’t feel like writing much. Really, I just want to watch The Grand Budapest Hotel again and soak up any morsels of the delightful confection I might have missed the first time.

But before that, a few words about exactly why I loved it so much, in the hopes that your appetite may be whetted enough to get you to the theatres, ready to sink your teeth into this delectable treat.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is Wes Anderson in all his glory. The sets are masterpieces, oddball works of ornate, pastel art. The cinematography is extraordinary, ditto the score (with musical mastermind Alexandre Desplat returning to Budapest from the Kingdom to work his magic once again). And the story, chock full of absurd characters and absurdist scenarios, manages to touch on human and historical truths, all in a thoroughly engaging, giggle-inducing manner.

Most of The Grand Budapest Hotel takes place in 1930s Europe, although it moves around in place and time, being a story within a story, several times over. A young girl reads a book of the entire account, which was written by a now-deceased author, whom we meet as an older man (Tom Wilkinson) and then as a middle-aged man (Jude Law). As Law, the young writer travels to the Grand Budapest Hotel, only to encounter the hotel’s fascinating, if lonely, owner Mr. Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham), who recounts the story of how he acquired it.

With that, the main story begins. It follows Mr. Moustafa in his youth, when he was a lobby boy who went by the name of Zero (Tony Revolori) and studied under the hotel’s expert concierge, M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes). M. Gustave is a spectacularly thorough concierge, even going so far as to take his patrons to bed—particularly the wealthy, elderly, female blonds. When one of those patrons is murdered (the mysteriously named Madame D., played by Tilda Swinton) and M. Gustave inherits her most prized possession, her greedy family is understandably suspicious. From there, Gustave and Zero embark on a wacky caper that makes its way across fascist-era Europe, into jail and down the snowy Alps near the fictional Republic of Zubrowska, where the Grand Budapest stands tall.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is as fanciful as Moonrise Kingdom, but even quirkier and much heavier. For all its whimsy and brightly coloured décor, the film’s historical backdrop sets some darkly hued undertones. Case in point: the ZZ officers who invade Gustave and Zero’s train compartment.

But Gustave refuses to bow down to the rising wave of fascism. He insists on preserving the “faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity.” Indeed, the Grand Budapest itself is a nostalgic nod to Old Europe’s refinement and romanticism. (Driving the point home, the film’s 1930s storyline is shot in the nearly square aspect ratio used in the golden oldie movies of yesteryear.)

Gustave runs the hotel with panache, leaving a haze of cologne and exquisite Mendl’s pastries in his wake. Shamelessly flirtatious and unfailingly polite (minus an f-bomb here or there), he manages to come across as that oh-so-rare creature: an honourable jackass. This spectacular combination is delivered courtesy of Fiennes’ brilliant performance. As Gustave, he’s staggeringly hilarious; his brand of straight-up comedy is perfectly on point and appears utterly effortless.

Fiennes steals the show, but he’s backed by a seemingly endless supply of impeccable actors, none above even the smallest cameo in a Wes Anderson film. In addition to those already mentioned, The Grand Budapest Hotel features an overwhelming ensemble cast that includes many Anderson favourites, not to mention mine—Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Harvey Keitel, Edward Norton, and Saoirse Ronan as Zero’s true love Agatha, the creator of those adorable little Mendl’s pastries that look as scrumptious to eat as the movie is to watch. (It’s a lot of fun to see Ronan in another fairytale-esque flick gone mad, after her outstanding turn in Hanna.)

All this to say I absolutely adored The Grand Budapest Hotel; I even managed to write a full review of it after all. Still, there is some small print to read: As soon as the credits rolled, a guy behind me in the theatre said, “That was the strangest, most boring movie I’ve ever seen.” Strange? Yes. Boring? Not in the least, not in my opinion. Maybe this movie isn’t for everyone. But if you’re a Wes Anderson fan, or even more generally an art fan, you should absolutely get thee to The Grand Budapest Hotel, post-haste. And you might want to bring along some pastries for the ride.

Divergent (feat. Isaac and Jonathan Walberg)

Monday, March 24th, 2014—FilmDivergent (USA 2014, Action/Adventure/Sci-Fi), Writers: Evan Daugherty, Vanessa Taylor; Director: Neil Burger

This Divergent review comes at the request of my eldest nephew, 11-year-old Jonathan. Together, we reviewed The Hunger Games and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, with his younger brother Isaac joining us for the second adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ franchise. So I guess Jon got a taste for it, which is pretty cool. And since I passed on reviewing the Ender’s Game adaptation with him, what kind of an aunt would I be if I didn’t step up for Jon’s next request?

Given that it was his idea, I wanted Jon to have a more active voice in this review, so I tasked him with outlining Divergent’s plot: “It’s about a dystopian society where, at age 16, children take a test to see what category they fit in. Everyone fits into one thing only, except those people who fit into more than one, who are called Divergent. Some people see them as a threat to the society. So the movie is about someone who is Divergent.”

Well said, Jon! To that I’ll add that the categories, or factions, are Abnegation, Amity, Candor, Dauntless and Erudite, and that the Divergent person who shows traits from multiple factions is Tris Prior (the excellent Shailene Woodley).

Divergent is based on the novel of the same name, which is part of a trilogy by Veronica Roth. The series draws obvious parallels to The Hunger Games franchise, among them: a strong young female protagonist who exists in a dystopian future and who helps lead the charge against a controlling system that denies individuality and restricts civil liberties; an ardent following at my nephews’ house; and, according to Jon, “really good first two books and horrible third books.” (His words, not mine; I still haven’t read the other books in the Divergent series, Insurgent and Allegiant.)

I prefer The Hunger Games, both in the story and in the telling. On top of what else the series explores, I find its additional commentary on our fixation with appearances, celebrity and others’ lives adds a significant point of interest, not to mention how well the reality show slant lends itself to a visual adaptation. And although I appreciate the notions Divergent explores, like our need to label people and the desire to conform, its world is somewhat underdeveloped.

My nephews think otherwise. (Evidently we diverge.) Both Jon and Isaac prefer Divergent to The Hunger Games adaptations, although they’re still big fans of both series. (And I still like Divergent, on the whole.)

“Divergent was really good,” says Jon. “I would say I liked it a bit better than The Hunger Games because it followed the book and they did everything really well. The actors were really good. For both series, the main idea of the plot is really interesting but I found Divergent way more action-packed.”

The movie does take some liberties with the novel, smoothing out a few of the rougher, non-PG-13 bits, removing or downsizing some extraneous characters and, in particular, shaking up the ending a little. But generally, I agree with Jon that the film follows the book quite closely—sometimes to its detriment. It felt a bit like the movie was plodding through each plot point; it was too long and not as well paced as The Hunger Games.

Jon, however, takes no issue with that. He likes that the movie has “no surprises” and is “almost exactly like the book.” He doesn’t find that boring, but rather a testament to its strength as an adaptation.

Isaac, now 10, read the book when he was eight, so he doesn’t remember it very well. His appreciation for the movie stems less from how faithfully it follows the book and more from the premise itself. “I liked Divergent a bit better than The Hunger Games because I think I like the idea better—choosing where you belong vs. playing games to the death,” he says. (Not that Isaac is opposed to violence in general; he also says “I liked when Four [the Dauntless trainer and Tris’ love interest, played by Theo James] beats people up.”)

Jon is a fan of Four, too, although he says Four was the only character who didn’t turn out the way he pictured him in the book. “There’s another book, called Lorien Legacies, where there’s a character name Four,” says Jon. “I pictured him like that guy.”

Four prompts an interesting insight from Jon about the (slim) illusion of choice created by the founders and governors of Divergent’s Chicago, where the story is set. “As Four was saying, he wants to be everything,” says Jon, referring to the scene when Four admits he wants to embrace the traits of all five factions rather than be only one thing. “So it’s like all the people are given the option to choose what faction they want to be in when they’re 16, so it’s almost like freedom. Except it’s not freedom because they can’t be more than one thing.”

I ask Jon and Isaac which faction they would choose if they had to pick one. “I did an actual test on the computer, the Divergent Aptitude Test, and I was Divergent,” says Jon. I tell him that’s probably the point of the test; beyond pure publicity, it aims to reinforce the trilogy’s lesson that we are all more than just one thing. “Yeah,” he says, “almost everyone who takes the test is Divergent. I was Divergent for the exact same things that Tris was in the movie.” (That would be Dauntless and Erudite, as well as her birth-faction, Abnegation.)

If Jon HAD to choose a faction, he says, “Amity would probably be the safest.” But “if Dauntless didn’t have that rule that if you’re below the line [i.e., don’t make the cut during initiation], you’re out, then it would be pretty awesome.”

Isaac has a similar thought. “I’d want to be in Divergent—but does that count or not?” he asks. Assuming it doesn’t count, he says, “If there wasn’t the ‘below the line, you’re out’ rule for Dauntless, I would be that. It’s the most fun.”

I ask Isaac if he would want to live in a world divided so rigidly by factions, and he says, “I would never want that to happen. I wouldn’t like that. I like how it is right now in real life. But it would be cool to try it out for a day, or something like that.”

As long as it’s just at the movies.

* * *

Thank you to Isaac and Jonathan for joining me once again in a movie review, and to their parents for helping arrange the interviews!

Enemy

Tuesday, March 18th, 2014—FilmEnemy (Canada/Spain 2013, Mystery/Thriller), Writer: Javier Gullón; Director: Denis Villeneuve

If you read my Prisoners review, you’ll know how much I’ve been looking forward to the release of Denis Villeneuve’s subsequent film, Enemy. In anticipation, I read José Saramago’s novel The Double, on which the movie is based. This was my second exploration of a film adaptation of one of Saramago’s works, having read and seen Blindness. But unlike with the first experience, this time I had trouble getting through the book.

In writing Blindness, Saramago took liberties with punctuation (i.e., he didn’t use much of it), but it’s even more extreme in The Double, where he spends countless pages detailing inanities in a confusing, repetitive manner. All that made for a bit of a tedious read.

Still, The Double does delve into interesting ideas about identity, perception, purpose and our very existence. So it was worth exploring. But for me, those ideas were better presented in Villeneuve’s film adaptation than in its source material.

In Enemy, as with most film adaptations, the story is pared down from the novel, offering a leaner, and in this case meaner, version of events. (One minor but notable difference is the protagonist’s name: Adam Bell in the movie is Tertuliano Máximo Afonso in the book, a lengthy moniker that its bearer loathes and that is repeated in full every time the character’s name comes up.) Enemy cuts to the chase—even if that chase leads you in circles, after your own tail.

So what’s the movie about? Well, that’s a little complicated, but I’ll start with what happens in the movie. We’re introduced to Toronto-based history professor Adam Bell (Jake Gyllenhaal), who goes about his dreary, repetitive life, trapped in a cycle of routine lectures (on the ways totalitarian states keep people down), mundane sex (with his girlfriend, Mary, played by Mélanie Laurent) and restless nights. His pattern is shaken up when Adam rents a movie, on a colleague’s recommendation, and discovers an actor who looks just like him.

Adam tracks down the actor, a man named Anthony Claire (also Gyllenhaal), who already operates under a dual identity, having the stage name Daniel Saint Claire. Anthony’s exterior matches Adam’s, but his interior harbours a much darker side.

The men confirm that they are one another’s exact double, complete with matching scars. From there, things really start to unravel, particularly when the men swap women without consulting their partners (Anthony has a six-months pregnant wife named Helen, played by Sarah Gadon; interestingly, he’s also been absent from his acting career for six months—perhaps while embracing a teaching career as Adam?).

Enemy does more than tighten The Double’s plot points; it takes liberties with events, trimming some here, adding others there. But it hits all the unmissable points.

The film also nails the novel’s creepy tone, capturing the feeling of being caught up in the minutia of daily life, of endlessness, pointlessness and powerlessness. Capitalizing on the poignancy of the visual image, as opposed to the written word, Enemy’s cinematography depicts a bleak, dingy cityscape, one that’s yellowed out somehow, like faded images—relics of the past, or a history destined to repeat itself.

Beyond its cinematography, Enemy incorporates a visual metaphor and representation of The Double’s twisted surrealism and sense of being trapped in a web. From the low-angle shots of streetcar wires that hang over the city like spindles, to the appearance of actual arachnids (for example, at an elite sex club, where men stare vacantly as naked women release live tarantulas from captivity), spiders are a recurring symbol in the film.

I don’t want to break Enemy down too much, both because I want to avoid spoilers and because I should watch the movie a second time before trying to really analyze it—the film bears repeating. But it’s definitely not for a lack of material to explore. Enemy, like Drive, is another great candidate for a film essay. Its script is loaded with double meaning and leaves even more open to interpretation than does The Double (as far as I can tell, anyway).

Whereas the book treats the two men, Tertuliano and António Claro, as being quite separate, the movie drops hints that they may actually represent two sides of the same person. We’re given clear evidence that they are two different people, but there are also suggestions to the contrary, letting the complexity and ambiguity of the novel’s themes emerge from the cluttered prose to rise to the surface.

Then there’s the significance of changing the title from The Double to Enemy. The focus is directed away from the notion of a doppelganger and toward the threat it represents, but who is the enemy here—the state? the self?

And so on.

There’s a lot to uncover, and it all culminates in a staggering ending; the final shot is a total WTF moment (and another departure from the novel, although it does bring to mind a line from The Double: “… sometimes dreams do step out of the brain that dreamed them…”). But after the initial shock wore off, I found it to be perfectly fitting with Enemy’s themes, absurdity and apparent quest to get the neurons firing. A more conventional conclusion might have been clearer, but it likely would have felt trite or unsatisfying. As it is, Enemy keeps its viewers dangling, and I think that’s exactly what the filmmakers intended.

Enemy is an interesting study in the possibilities of moving from page to screen. And while its tone, cinematography and trippy dream sequences are reminiscent of the Davids (Cronenberg and Lynch), more than anything else, the artistic choices behind Enemy demonstrate Villeneuve’s own astonishing range; to go from Maelstrom to Incendies to Prisoners to this is quite incredible.

Enemy also features another of Villeneuve’s fantastic casts. Laurent, so great in Inglourious Basterds and Beginners, is in fine form. Gadon, who was excellent in A Dangerous Method, is at least as good in Enemy; her performance earned her a Canadian Screen Award for Best Supporting Actress. (Interestingly, Gadon was also one of the panelists for this year’s Canada Reads competition, defending Kathleen’s Winter’s book Annabel.)

As strong as the other actors are, the film rests on Gyllenhaal’s shoulders, requiring him to do double duty as both protagonist and antagonist (or are they one and the same?). He’s more than up to the task, proving yet again that he’s one of the finest actors working today (see If There Is I Haven’t Found It Yet).

With Enemy, Gyllenhaal also reinforces what a remarkable duo he makes with Villeneuve. I look forward to their next collaboration; what form it will take is anybody’s guess.

* * *

For more on the great work of Denis Villeneuve, see my Kickass Canadians article.

Winter’s Tale (feat. actor Alan Doyle)

Friday, February 21st, 2014—FilmWinter’s Tale (USA 2014, Drama/Fantasy/Mystery), Writer/Director: Akiva Goldsman

Winter’s Tale is a fantastical story about love overcoming odds and overpowering evil, a story that defies the linear boundaries of time and embraces magic, miracles and the notion of destiny.

Based on Mark Helprin’s novel of the same name, Winter’s Tale features Colin Farrell and Jessica Brown Findlay as star-blessed lovers destined to find one another, and Russell Crowe as Pearly Soames, a demonic gang leader on a quest to stop them.

The film also features Alan Doyle, who happens to be the newest Kickass Canadian, as well as Great Big Sea’s frontman and a regular on TV’s Republic of Doyle. In Winter’s Tale, Alan plays Dingy Worthington, an “Irish ruffian” and one of Pearly’s lieutenants. The movie marks the third time Alan and Crowe have teamed up for the camera; Alan played Allan A’Dayle to Crowe’s Robin Hood in the 2010 Ridley Scott film, and later acted with him on an episode of Republic of Doyle.

I had the great fortune of talking with Alan about his experience making Winter’s Tale. But before we got into the movie, the accomplished musician caught me up on where his upcoming solo CD is headed, having recently returned to his St. John’s, Newfoundland home after a musical jaunt to the U.S.

“I recorded a bunch in Nashville and a bunch in Los Angeles,” says Alan. “I got to work with some old friends and some new friends. It was awesome.”

When I interviewed Alan earlier this month for Kickass Canadians, he still hadn’t decided on the direction his second solo album would take. Now, he’s a lot closer to making that decision.

“The more I think about it, the more I’m comfortable with the record being an honest representation of where my head is, which is kind of in 12 different places,” he says. “I’ve never really been afraid to have rock ‘n’ roll songs sitting next to folk songs. If the record ends up having a little section that’s very pop and another section that’s country and another section that’s rock ‘n’ roll, that’s totally fine with me.

“I’m not sure people put on records and listen to them beginning to end anymore. I think people like hearing their favourite singers sing different kinds of songs.”

Alan’s recent recordings kept him from catching the Winter’s Tale premiere in Los Angeles, but he did find time to see a regular theatre screening after its February 14, 2014 release. He was pleased with the results.

“It was really good, man,” says Alan. “I thought it was beautiful in a really classic, old school kind of way.”

For his role in the film, Alan shot about 21 days over a four-week span (the entire production took approximately two months). He says there were plenty of challenges throughout the relatively short shoot. For one thing, it was shot entirely in greater New York City during autumn 2012, when Hurricane Sandy blew through. For another, the film features plenty of busy public venues.

“There were no typical days on that shoot, because we were shooting in New York City,” says Alan. “It’s not like you’re on a sound stage for most of it, where you can just roll camera whenever you want.”

Case in point: the scenes they shot in Grand Central Station.

“Of course Grand Central Station never closes, so how do you shoot in there?” he says. “We shot those scenes one evening in between arrivals and departures of trains, so we would hold (the public) for 30 seconds and we’d shoot it one way and then we’d wait for another 15 minutes and reset and wait for the trains to leave and then we’d go again. Those are the challenges of shooting; it’s very difficult.”

I ask Alan if he found it challenging to concentrate on his performance during such trying circumstances. Impressively, the answer is “No,” but he credits his co-stars for making it easy to stay in character.

“I was always either with Russell or Colin, and they’re such pros,” says Alan. “They’ve had so much experience developing the arc of their performance in the most imperfect surroundings. That’s one of the hardest jobs an actor has, is to do all the stuff they intended to do, in conditions that are never ideal. They have to be able to deliver no matter what.”

Alan attributes this ability in his Winter’s Tale cast mates to being thoroughly prepared. For instance, he says, “there’s nobody more ready to go to work than Russell Crowe. That’s the reason why he’s been in the business for so long and remains at such a high level—because he works the hardest.”

Of course, Alan had plenty of prep work of his own to do. His character, Dingy, handles a gun, so Alan worked with a weapons trainer to get the technique down. He’d had similar training for Robin Hood, but still found it a challenge to master the necessary subtleties for Winter’s Tale.

“When you’re firing a weapon, it’s hard if you’re not used to it to not look at it while you’re shooting,” says Alan. “Without giving too much away about the movie, the character I played had shot a gun many times, but the real me, I play the mandolin!

“So it’s just another skill set, (being able to master skills you’ve never applied in real life)… It’s the skill set that separates me, a very novice actor, from the other guys who have many skills they’ve picked up over the years—whether it’s gun work, dancing, axing, all the skills that you learn on the job. They’re awesome at it.”

One of the biggest lessons Alan learned from working on Winter’s Tale had nothing to do with the action sequences. For him, it was all about stillness.

“In the film, the love story and the power of love is the central theme, and of course (characters like Dingy and the rest of Pearly’s gang) are all the antithesis of that,” says Alan. “We’re bad and we have to appear so in a very quiet way, especially when we’re in the background. So how do you do that?

“It was really a lesson for me, because I’m not usually a quiet person and I’m not usually an evil person, I don’t think, but (I had to learn to harness) the power of stillness and overcome the difficulty in doing nothing. There’s an awkwardness and uneasiness that you create when you’re just quiet and still, and it’s so powerful.”

Looking ahead, Alan is excited to apply his newfound skills and knowledge to his next acting role, as Senator Gideon Robertson (“another bad guy”) in Canadian filmmaker Danny Schur’s production of Strike!. Filming begins this summer, and the movie is slated for a spring 2015 release.

Beyond Strike!, Alan says he’d love to do something along the lines of “a weird, quirky Coen brothers movie.” He mentions the filmmakers’ latest feature, the excellent Inside Llewyn Davis, starring his friend Oscar Isaac, as a great example of what can happen when a movie plays to an actor’s particular strengths.

Oscar has sung for the movies before, including in the 2012 film 10 Years. That time, he and Alan co-wrote a song for Oscar’s character to perform, and the experience left a big mark on Alan.

“I think it would be an amazing thing to find a role where you can sing a little bit and have all your talents out there,” he says. “That would be so much fun to do.”

* * *

Winter’s Tale is in theatres now. A big THANK YOU to Alan for making time to chat with me about it!

The Lego Movie (feat. David, Isaac, Jonathan and Sean Walberg)

Tuesday, February 18th, 2014—FilmThe Lego Movie (USA 2014, Animation/Action/Comedy), Writer/Directors: Phil Lord, Christopher Miller

A few years ago, back when I had only two nephews, I was on a quest for real Lego—those loose pieces that come in all sorts of shapes, colours and sizes, the kind you could build into whatever you wanted, the kind that didn’t come with a set of instructions and a specific purpose in mind. I wanted to give my first nephews, Jon and Isaac, the kind of Lego I grew up playing with. But all I could find in my local toy stores were Lego kits, designed more for crafting predetermined ships or boats or planes than to stimulate the imagination. It wasn’t until I stopped in at Toys “R” Us in Times Square that I was able to find a box of the prized pieces.

Today, I’ve got three nephews playing with that New York City Lego (young David joined the gang about six years ago). I’m proud to say that all of them prefer making their own Lego creations to sticking with the instructions. They love the kits, too—they’re a new generation, after all—but once they’ve finished following directions, they take the finished product apart and start inventing their own versions.

As much as my nephews and I love Lego, we weren’t on board right away with the idea of a Lego movie. When Isaac and I discovered the movie’s poster during his recent visit to Ottawa (the boys live in another province), we were left wondering what on earth the plot would be about for such an obvious marketing piece.

Jon had the same doubts, although they were quickly turned around once he saw the movie last weekend. “When I started watching it, I was thinking, ‘How can a movie about Lego have a plot?’” he says. “And then after, I realized it was pretty cool how they took Lego and made it into a huge movie.”

It’s a huge movie, indeed. The Lego Movie comes from the genius writer/director team behind Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. Here, they’ve created a brilliant, self-reflexive animated flick that, in the words of fellow Lego junkie Thomas J Bradley, “perfectly captures the ideas of Lego.”

So what is the plot? I won’t reveal the overarching premise, but the main story follows Emmet (Chris Pratt), a regular Joe Lego man presumed to be the “Special” destined to save the world from the evil Lord Business (Will Ferrell), who rules over all things Lego and insists that everyone always follow the instructions. Emmet joins forces with a fantastic group of rebel figurines, including Wyldstyle (Elizabeth Banks), Batman (Will Arnett), Spaceman Benny (Charlie Day) and the wizard Vitruvius (Morgan Freeman). Standing in the way, alongside Lord Business, is Liam Neeson’s conflicted Bad Cop.

The Lego Movie holds together with shrewd observations about the real world and very clever plays on sayings, words and product names. It turns ideas on their heads and offers hilarious insights into the way children interpret their surroundings—all without alienating the parents in the audience.

Sean, my brother-in-law, dutifully took the boys to the movie, but he was pleasantly surprised by how much he himself enjoyed it. “There were a lot of adults laughing their heads off in the movie,” he says. “It was well done.” Sean also commented on the “nostalgia factor” the movie tapped into. For example, Spaceman’s faded logo, or his broken chin strap. “That was what would always break first on those things.”

There’s no question that The Lego Movie is an unabashed marketing campaign. The filmmakers deliver a fabulous one-two punch, targetting grown-up kids who were raised on Lego, just as much as the kids who play with it today. But they’ve also built a smart, inventive flick that shows what’s at stake when imagination is squelched for the sake of compliance, and concludes perfectly by driving home the idea that one person’s happy ending isn’t necessarily the same as everyone else’s.

More to the point, The Lego Movie is piles of fun. It’s hilarious and visually awesome, and it makes it very clear that playing with Lego (or at least being creative, taking risks and believing in yourself) forms the building blocks of a happy childhood and an accepting, inspired adulthood.

I don’t want to spoil the surprise by rattling off too many examples of what’s so funny and clever about the movie. So I’ll keep it to just a few of the best bits, according to my nephews and me.

David: “Everything is AWESOME!!! I liked the Lego lava at the beginning. It’s so cool when it boils, Lego hot stuff goes flying up in the air. They used a lot of Lego pieces for that. Except it’s not so realistic Lego. I love how that spaceship guy was screaming ‘SPACESHIP!’ the whole entire time he was flying; it was so funny. How does that work, Lego people talking? I guess people were dressing up as Lego blocks.”

Isaac: “I liked the rocket ship guy. And the Millennium Falcon. I thought it was funny. The ending was really funny. I don’t know what my favourite part is; I just like building Lego. I just finished building a Lego castle, it’s like six little rooms, each side of it has a roof and then a base on top. It has walls and a sniper tower. And I added more to the Lego ISS.”

Jonathan: “I really liked the part where the bad cop keeps changing into a good cop. I liked the plays on terms. And the ending was pretty funny. I read a lot about it in Isaac’s Lego magazine so I kind of knew what was coming. It was really good.”

Jon with one of the “secret” animal villages we built; no Lego involved, but each of the figurines would slot into a Lego world

Me: “I loved Batman’s song, Untitled Self Portrait: [To the barking beat of the Batmobile’s subwoofers] DARKNESS. NO PARENTS. SUPER RICH. KINDA MAKES IT BETTER.”

* * *

Thank you to Rebecca and Sean for casting aside the instructions and putting together the best nephews an aunt could ask for. They’re colourful, animated and totally awesome.