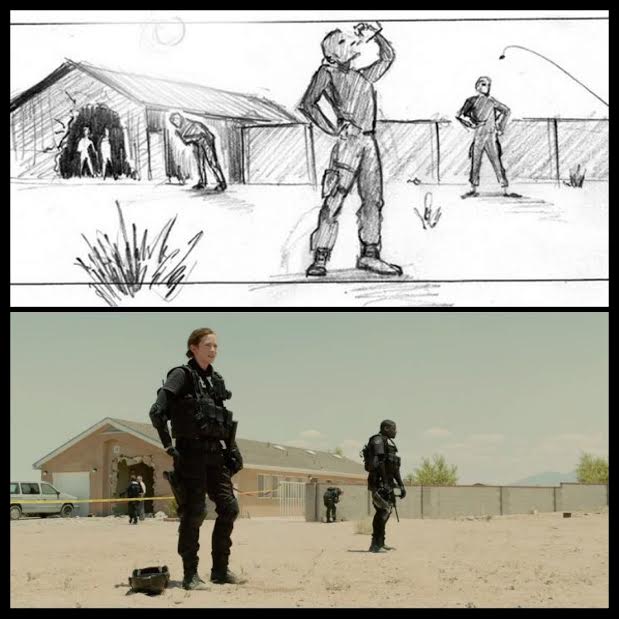

Sicario (feat. storyboard artist Sam Hudecki)

Tuesday, October 6th, 2015 4:01 pm—FilmSicario (USA 2015, Action/Crime/Drama), Writer: Taylor Sheridan; Director: Denis Villeneuve

Breathtaking. That’s probably the best word to sum up Sicario, if I had to choose one. The film had me in its grip from beginning to end, closing in tighter with each pulsing beat.

Sicario is about idealistic FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt), who is recruited to join a covert government task force looking to curtail the drug war that rages around the Mexican–U.S. border. It’s also about cultures in crisis, and an increasingly violent world that’s showing signs of growing numb to death and destruction, and that believes more and more that the end justifies the means.

The film begins by explaining the origins of its title: sicarii was the name given to zealots in ancient Jerusalem who fought off the Roman invaders to protect their homeland; in Mexico, sicario means hitman.

That introductory text is the first heavy hit the film delivers—along with its unnerving score. Right away, Sicario makes it clear that it intends to throw open the box full of questions, each of which has no clear answer. Which land is the homeland? How can we truly tell the invaders from the protectors?

The deeper Kate delves into the operation, and the further she dives into Mexico, the more she realizes just how much darkness she’s treading in. Team leader Matt Graver (Josh Brolin) of the U.S. Department of Defense doesn’t even do Kate the courtesy of operating on a “need to know” basis; it’s more of a “deign to let you know” scenario. The cryptic Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), who is also part of the unnamed team, presents an even bigger mystery; he’s a “ghoul” whose origins and intentions remain in the shadows as long as he can keep them there. (Dropped off the edge again down in Juarez…)

With Sicario, director Denis Villeneuve revisits some of the territory he explored in Prisoners: How far should one go in pursuit of justice or revenge? Is it okay to take the law into your own hands if the truth is tangled up in red tape? And when is violence acceptable? Where is the line that separates victim from perpetrator? The questions keep coming.

From what I can tell, to Villeneuve, violence is only acceptable when it exposes the damage done; never when it’s presented as entertainment. In the film’s opening sequence, Kate and her partner, Reggie Wayne (Daniel Kaluuya), lead a deadly raid on a house in Phoenix, Arizona. They’re looking for hostages, but instead they find corpses stacked vertically between the walls—plaster tombstones sealed by bleak paint jobs.

Even after Kate flees the house, standing in its backyard of dust as she and her team reel from the discovery, we’re not safe from what stands inside. Villeneuve takes us back to glimpse ever closer at the faces of those who fell victim to the drug cartels.

The directorial choices that make the opening sequence, and all the rest, so impactful are why Sicario left me breathless. It showcases some of the best filmmaking talents working today, led first and foremost by its profoundly gifted and ruminative director.

Aside from Villeneuve, the person who might be most responsible for the film’s chest-clenching effect is composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, who delivers a stunning score full of cello, percussion and electronics. His music haunts the movie, snaking and rattling through scenes as it makes its way from simmering to seething.

Lighting master Roger Deakins pulls off extraordinary feats of cinematography, particularly in low-light settings (including one incredible sequence in a tunnel, shot using night vision and thermal-image cameras). Taylor Sheridan’s script is brilliant (amazingly, Sicario is his debut screenplay). In the lead roles, Blunt, Del Toro and Brolin are excellent, each as skilled as they are talented. Editor Joe Walker pulls it all together, making for taut, tightly wound coil of film that threatens to snap off the spool at nearly every frame.

Those are some of the headline names associated with Sicario. But as with any film of this scale, there are of course many more artists who played a critical hand in making it happen. One of those people is storyboard artist (and Kickass Canadian) Sam Hudecki.

Sicario is Sam’s third collaboration with Villeneuve, after Enemy and Prisoners (and before next year’s Story of Your Life and their current collaboration, the Blade Runner sequel). I worked with Sam many years ago, after we graduated from Queen’s University’s film program, when he was 1st assistant camera on my short movie Sight Lines. He’s now in the midst of a pretty thrilling project, but he graciously made time to chat with me for this review and share his behind-the-scenes insights.

Sam spent three months in pre-production on Sicario, working alongside Villeneuve in New Mexico. “I really love working with him,” says Sam. “I think we established a great working relationship, and (storyboarding with him is) my favourite creative process to be in.”

It’s a process that always begins with a conversation. Going back to Sicario’s opening sequence, Sam says there was a lot to talk on that front. “Denis and I had many conversations about the nature of violence. Do you show a grenade before it goes off, or do you witness an explosion and the suddenness of that explosion? (The way we approached violence in the film) was a decision that came out of a lot of discussion around the potential impact of that opening sequence.”

There’s another sequence in the film that stands out to me, one that’s equally impactful. After the special ops team travels to Juarez to capture one of the top players in the Mexican cartel, they bring him back for “questioning” at the hands of Alejandro. Alejandro sidles down the hall and into the interrogation room, whistling all the while, toting a jug of water. When he approaches the captive, Alejandro doesn’t strike him; instead, he saunters up so close to him that the looming attack starts to feel almost intimate. It’s one of the most intimidating moments I’ve seen in a film.

Mercifully for the viewer, if not the captive, the violence takes place off-screen. We don’t need to witness it; Alejandro’s quiet menace bares all.

From everything I have seen, Villeneuve displays that sensitivity toward violence in all his films. He also shows great empathy toward women. I touched on that in my Prisoners review; to me, it’s a trademark of the director’s approach, and one I value very highly. (For more on this, see my Kickass Canadians article on Villeneuve.)

He does it again with Sicario, which strongly emphasizes Kate’s point of view in a male-dominated world. So it’s somewhat shocking (from an artistic perspective, if not a business one) to learn that backers who initially looked at the film wanted Kate replaced with a male protagonist. To make the lead character a man would completely change the story. It would be to lose Kate’s inherent vulnerability, the eyes through which we see the story—those of an outsider.

Fortunately, with Villeneuve involved, there was no need. According to Sam, “Denis brought a lot of attention and sensitivity” to Kate, something Sam himself appreciated.

“I love the fact that the protagonist is a woman,” says Sam. “She’s in a position that would be tough for anyone, but it’s particularly tough for Kate because she’s a woman on a (dangerous, questionable) mission led by men, and she has strong ideals. So her point of view was certainly something we were very acutely aware of in our approach. As (the team goes) into Mexico, we’re very aligned with Kate.”

Adopting an outsider’s perspective was a key factor for Sicario, given that the crew couldn’t film in Juarez, where many key scenes were set. We see it only from a distance, which is fitting given that our impressions of the city are framed by someone who doesn’t truly understand what she’s being drawn into. “You only get to know a hint of what’s really going on there, and that’s as far as we could take it,” says Sam.

Shooting in Mexico, if not Juarez itself, was important to the filmmakers because they very much wanted to create an authentic depiction of the area. “We looked a lot at what is really going on,” says Sam. “And while there’s artistic licence, (the film) comes from a place of being very grounded in reality.”

Still, Sam stresses that Sicario isn’t intended as “an advisory of any kind about Juarez. It’s more of a meditation about conflict (in general).”

The subject matter isn’t surprising when you consider the source; Villeneuve has become known for his penchant for exploring the darker side of humanity. But that doesn’t mean the director himself is mired in gloom.

“I read somewhere that people (assume) he must be a very dark and depressed person,” says Sam. “It’s not true; it’s actually quite hilarious and tremendously enjoyable to work with him.

“The purpose of storyboarding is just to get everyone on the same page, and that page is Denis’ vision—his dream of the film. My job is to help unlock the dream and get some of that on paper. So it’s always kind of a first blush, and I know that when Denis and I can look at each other and think, ‘This is exciting,’ I know that it will be.”

I’m still catching my breath.

* * *

Thank you, Sam, for sharing your time and thoughts with me. Here’s a shot of us and the Sight Lines cast and crew, on set in 2002 (Sam’s left of the camera; I’m to its right, in jeans):

Keep an eye out for the next two collaborations from Sam and Villeneuve, two of Canada’s greatest film talents—Arrival, set to release in early 2016, and the Blade Runner sequel, scheduled to start shooting in summer 2016.

* * *

From Tori Amos’ ‘Juarez’:

Dropped off the edge again down in Juarez |“Don’t even bat an eye | if the eagle cries,” the Rasta man says, just cause the desert likes | young girls flesh and | no angel came.