Archive for January, 2019

Vice (feat. production designer Patrice Vermette)

Thursday, January 24th, 2019—FilmVice (USA 2018, Biography/Comedy/Drama), Writer/Director: Adam McKay

Last month, a few days after the start of what has become the longest government shutdown in U.S. history, Vice hit theatres. Just as writer/director Adam McKay’s The Big Short exposed corruption in the U.S. mortgage market, Vice explores the same beast in politics—American in particular, but also the political machine in general. In this film, though, the beast has a name: Dick Cheney (played magnificently by Christian Bale), widely known as the most powerful Vice-President in American history.

Vice lifts the curtain on Cheney’s role in American politics, starting with his internship under then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell) and ending with his eight years as Vice-President to George W. Bush (Sam Rockwell). It examines the personal motivations that drove Cheney to become a “servant to power” and underscores the tremendous, lasting impact his vice-presidency had on the world, especially regarding the Iraq War, Big Oil and foreign policy.

Sound a little dry? It’s not, because it’s dressed in McKay’s trademark fashion: quirky, comedic asides; intercut footage of actual events; a charismatic narrator along for the ride. Like The Big Short, Vice succeeds in packing a heavy, information-packed punch while also tickling the funny bone. In recognition of that agile feat, the film was recently nominated for eight Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay for McKay, Best Actor (Bale), Best Supporting Actress (Amy Adams as Lynne Cheney), Best Supporting Actor (Rockwell), Best Makeup & Hairstyling and Best Film Editing (Hank Corwin).

For any film, success on that level requires an incredible amount of work from a huge team of people. When the film spans five decades, from the 1960s to the early 2000s, and includes more than 200 sets from locations as far flung and diverse as Wyoming, Texas, Italy, Vietnam, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iraq, the United Nations Headquarters, the White House, the Pentagon and many more, it becomes a Herculean effort. Add to that challenge the fact that Vice was shot in just 54 days and that every scene had to be shot in and around the Los Angeles area, and you’ve got what might seem like an insurmountable task.

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

Except that McKay chose his team from among the very best. I had the privilege of talking to one of his key players about exactly how they were able to pull off what they did with Vice: Patrice Vermette, the Canadian Screen Award nominated (Enemy), two-time Academy Award nominated (Arrival, The Young Victoria), Kickass Canadian production designer. Patrice graciously took time to chat with me from Budapest, where he’s currently in pre-production on a new adaptation of Dune (part one of two, due out in 2020). The project reunites him with his frequent collaborators, director Denis Villeneuve and storyboard artist Sam Hudecki. “The family is back together again,” says Patrice.

Patrice first read the script for Vice in the midst of the 2017 Oscar season, when he was nominated for Arrival. Right away, he was floored. Or, more accurately, ceilinged; one of the comedic scenes had him literally jumping for joy on the bed. “The script was really the best script I have read in my life,” he says.

The opportunity to work with McKay was also a major attraction. “I loved The Big Short for multiple reasons,” says Patrice. “First of all, it’s entertaining, but it deals with a very, very serious subject. Adam is so politicized and I think it’s part of his mission right now, after working on comedies, to use the talent he has as a storyteller to (help) people understand complex concepts. The way that he treats (each subject), it’s very unique.”

Patrice himself is always a keen student of whatever subject his current project revolves around. From royalty to aliens to drug cartels, he’s fascinated by learning, as much out of genuine curiosity as by the desire to get every detail right on his films. With Vice, he was eager to learn more about American politics because of how pervasive they are; whether or not you live in the United States, you’re most likely impacted by the country’s political decisions, to some degree.

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

But Patrice was also fascinated by the script because of how it shows that politics in general “have been hijacked. I don’t think it’s just the United States; it’s everywhere in the world, at different levels. Now, business techniques like focus groups are extremely useful for governments to sell policies that are unpopular… They use the same techniques as advertising companies and entertainment businesses, and it’s very bizarre; all the interest groups are extremely influential because they put so much money into getting people elected. It’s quite frightening.

“With movies, of course there’s an entertainment aspect to it, but if we can also deal with subjects that make people aware of certain aspects of the world they live in, it’s even better. When I read the script for Vice, I thought it was a perfect example of that; entertainment mixed with important subject matter, not just pure entertainment.”

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

Taken as he was by the script, Patrice always tasks himself with the job of “going deeper than just the written words.” As a production designer, he’s after the visual story between the lines on the page—the locations, sets and props that will project the script’s mood onto the screen and reflect it back into our hearts.

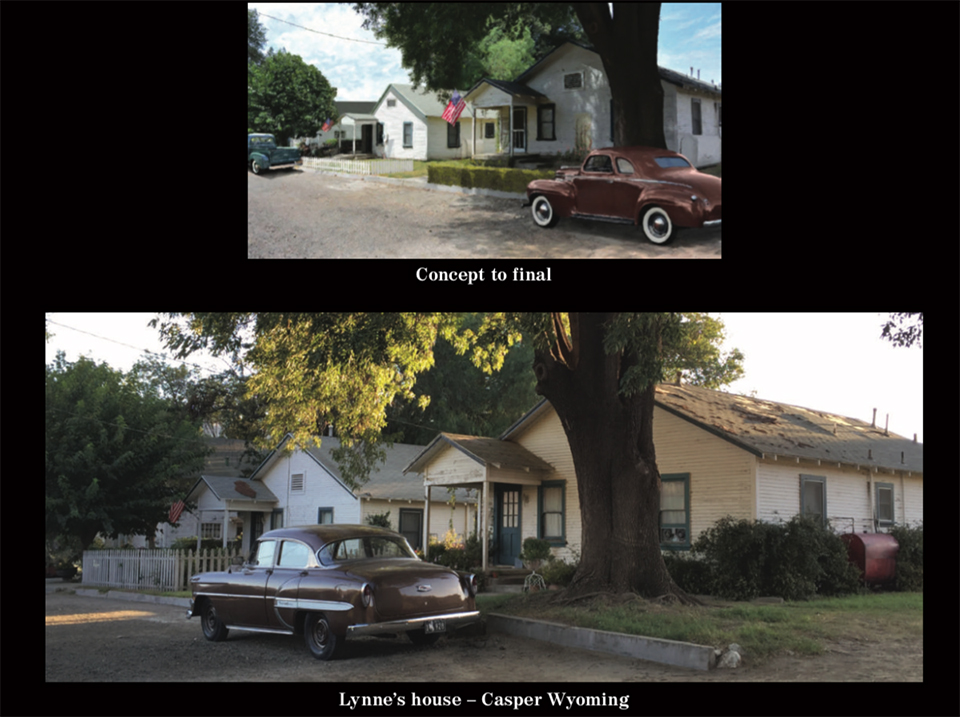

For him, the process begins by creating mood boards that capture the feeling he plans to convey on each location. With Vice, everything had to be shot near Los Angeles, as requested by Bale, who wanted to stay near his family throughout production. “No Christian, no Cheney,” says Patrice. “He’s amazing in the role. He’s an awesome guy, as well.”

So, Southern California it was. Patrice, along with McKay, location manager John Panzarella and cinematographer Greig Fraser, set about securing the best spots for each scene. Given the vast list of locations, that meant shooting several scenes on sound stages.

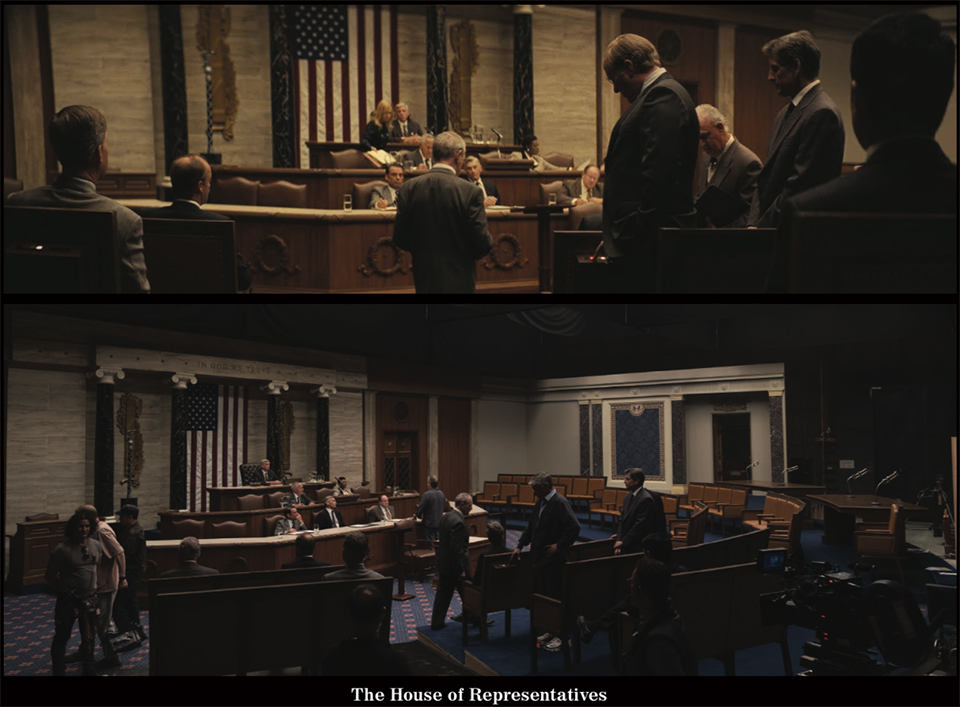

“There were some inevitable sets that had to be shot onstage because we would never find locations for those,” says Patrice. “Obviously everything that takes place in the White House, the UN Headquarters, the Supreme Court—all these things that are well documented are obvious builds because people will know if we try to pretend that we’re at the Supreme Court and we’re not, and we want to be as accurate as we can.”

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

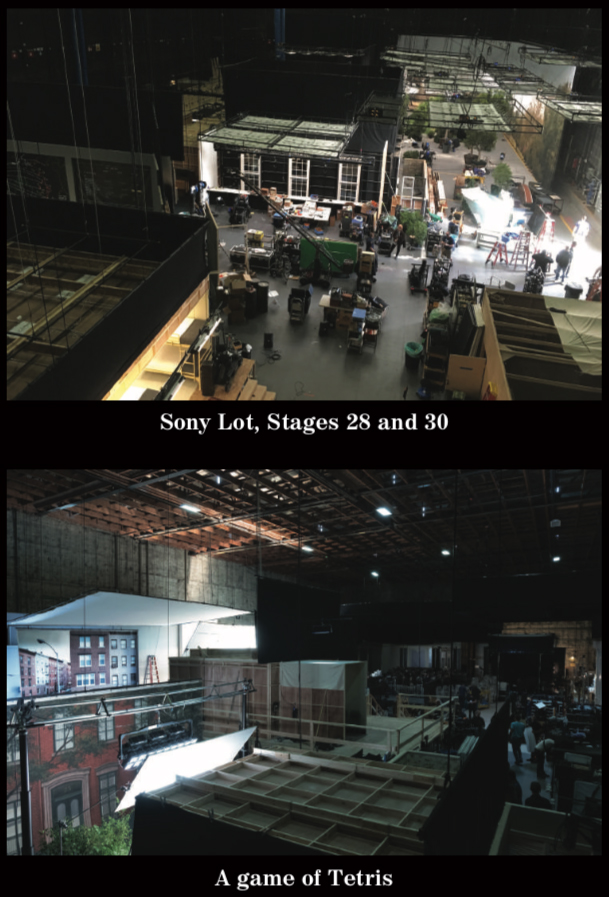

To that end, the team decided to create one-wall or sometimes two-wall sets, so they could make each scene as believable as possible within the confines of Sony’s sound stages. “It became a huge Tetris game. It was quite a challenge for my supervising art director, Brad Ricker.” The film’s schedule also dictated that some of the sets be quickly redressed to serve as multiple locations within the same shooting day.

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

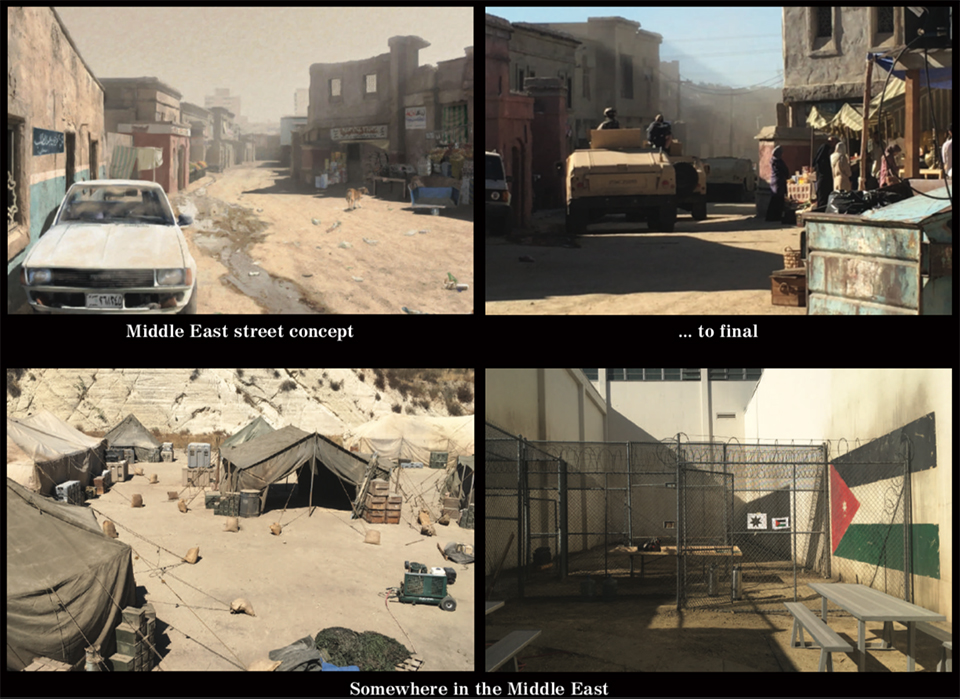

For other scenes, Patrice and the crew were able to find suitable stand-ins. “In California, the landscape is quite extraordinary,” he says. “We found mountainsides to match Afghanistan. We found a film ranch [Santa Clarita’s Blue Cloud Movie Ranch] in which there were partial sets of Iraq, and we built around that, enhanced it to shoot our scenes… There was a very flat beach around Santa Monica, and at a certain level you don’t see the sea, if the camera is low enough, so one angle works for Saudi Arabia.”

Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

Still, it was demanding to find locations that met with the team’s high standards. Dressing LA to look like Milan, for example, was particularly difficult. “LA doesn’t look anything like Milan. But we made it work. It was a great challenge but also a fun challenge.”

Beyond the locations, he also took great care to ensure that each set helped further the story. He was thrilled to reteam with set designer Jan Pascale, with whom he collaborated on Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario. “Jan is extraordinary,” says Patrice. “We share the same passion and attention to detail, and I love her dearly.”

That commitment to detail is unwavering. But it doesn’t mean he intends his choices to outshine any other element of the films he works on. “I think production design should be invisible. (With period pieces), I try to match the reality of the era without it being a parody. It needs to be real and discreet and subtle. I think ‘less is more’ is always the right approach.”

He takes that subtlety so far as to incorporate what he calls subliminal storytelling into his production design. For Vice, At McKay’s encouragement, that included visual references to the military, the petroleum industry and “the image of the cowboy and the Great West.”

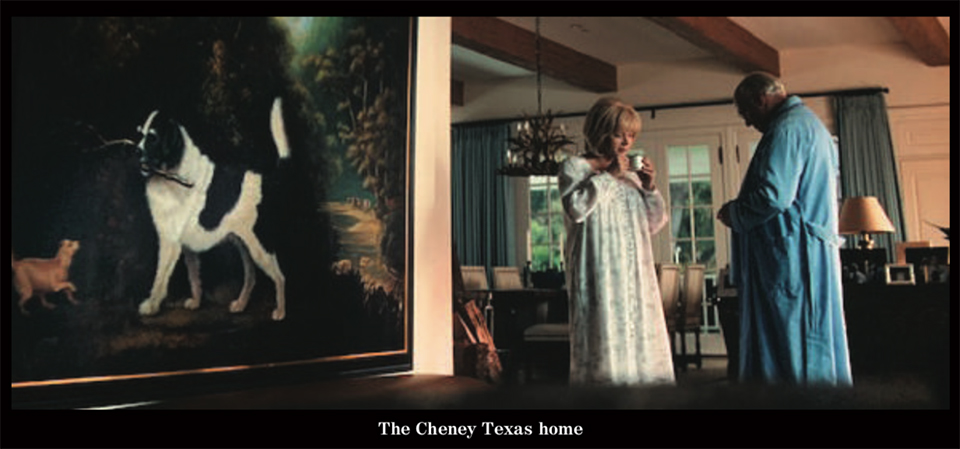

Patrice also looked for opportunities to add little bits of humour, for those of us who are quick enough to notice. In the scene where Cheney gets the pivotal phone call asking him to consider the vice-presidency, Patrice placed a painting prominently on the wall. It’s an image of two dogs—a big one holding a stick and a smaller one looking up at the bigger dog, pining for the stick. “We made the big dog look a bit like Dick Cheney and the smaller dog like George W. Bush,” says Patrice. (The devil is in the details…) “It’s the fun that I have on every movie; I do things like that.”

With Amy Adams, Christian Bale; Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

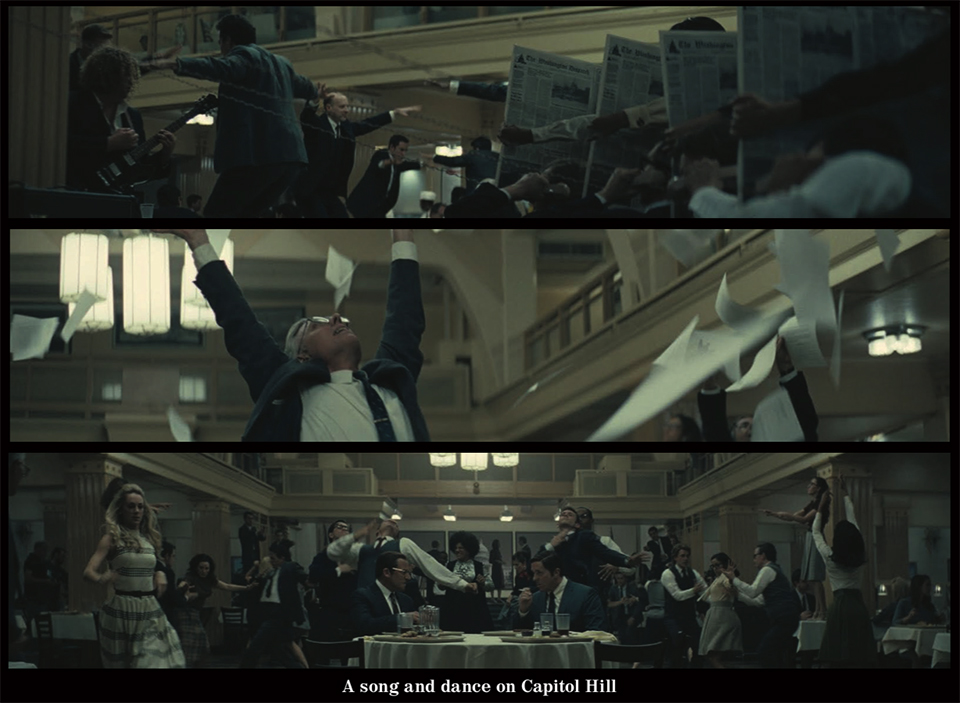

You can be sure that he put just as much attention and devotion into every other part of Vice’s production design—even the parts you won’t see in the final cut. There’s the scene that made him jump up and down on the bed when he first read the script: a musical interlude set in the Capitol Building. And the Nelson Rockefeller side storyline. “Every movie leaves scenes on the cutting room floor. There were some very, very hard choices, but in the end it’s all for the better because it makes a better, tighter movie.” (And there may still be hope that we can see the omitted footage. Says Patrice, “I hear that Adam wants to add some of the cut scenes when they release the Blu Ray and DVD.”)

With Steve Carell; Image courtesy of Patrice Vermette

One sequence that Patrice was particularly sorry to see go was set in the 1950s, when Cheney witnesses his grandfather die of a heart attack. The neighbourhood outside the grandfather’s house features the cookie cutter homes built just after WWII that were “made to realize the dream that everybody could own an affordable house. Back then, the plan actually worked. They created the suburbs and it was relatively affordable, although (the houses) all looked the same.”

He planned the location to mirror similar houses shown later in the film, at a life-altering moment for the narrator, played by Jesse Plemons. “So many years later, those houses that all look the same are all built with crappy materials and are all overpriced, and unfortunately people are now all being sold the dream that everybody can live like a king, in houses that are too expensive for their means,” says Patrice. “It’s another example of how that concept totally derailed into making profits for dream sellers, which (Adam addressed) in The Big Short. It was important for me to include those cookie cutter houses, (because the scene was) in the same era that they were being taken back by banks.”

With such intense focus on every scene in each project, I’m amazed at Patrice’s ability to stay fresh throughout the massive productions he takes on. His current shoot for Dune will run through to August of this year, keeping him away from his family, based in Montreal: his wife, painter Martine Bertrand, and their 17-year-old daughter and 15-year-old son. That, he says, is the hardest part of filmmaking. “But that’s how it’s been even since before the kids. My wife was the one who was travelling all the time in the 90s, working in Europe as a costume designer for stage. Then I started travelling all the time, first working on commercials and then the movies. So, we’re kind of used to that, it’s kind of our family (way), but it’s still hard.”

There’s also the mental exhaustion that must come from continually tapping the creative well to such great depths. “Trying to sleep is sometimes very, very difficult,” he says. “But (the key is to) never forget to take moments for yourself. My thing is, I love food and when I’m away from Montreal I find my little oases, which are restaurants, and I like to go out every night to eat good food. That’s my little treat at the end of the day.” The day of our interview—a Sunday, but he’s working anyway—his dinner plans are to eat at Indigo, “a great Indian restaurant in Budapest.”

Of course, those creature comforts along the way aren’t the only reward for giving so much of himself to his career. He is deeply passionate about working on creative, significant projects that have the capacity to change minds, even lives. To make movies that matter.

“I hope with a movie like Vice, obviously it talks to the already converted. But if there are a few people who realize that’s how (the political system) works—if they stop and say, ‘Wait a minute, is that for real? Is that how it works?”—I think if there’s a few people who realize that or ask that question or become more aware of how things are being played, and not just about the Iraq War but about politics in general, I think the movie will have reached its goal.”

Vice is in theatres now. Good luck to the entire team at next month’s Academy Awards.

* * *

A big thank you to Patrice for so generously sharing his time and insights.

Thanks also to Isaac for joining me at the movies. I don’t get to the theatres much these days, and going with one of my nephews makes it all the more special!