The Babadook

Wednesday, August 24th, 2016 8:44 am—FilmThe Babadook (Australia/Canada 2014, Horror), Writer/Director: Jennifer Kent

I took my time getting to The Babadook, but this one is definitely a case of “better late than never.”

Horror is a genre I tend to avoid. I hate gratuitous violence and don’t like being scared just for the hell of it. The Babadook is horror I can handle; instead of cutting up bodies, it dissects psyches.

Specifically, the film looks at the strained relationship between widowed mother Amelia (played beautifully by Essie Davis) and her son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Amelia’s husband died in a car accident while driving her to the hospital for Samuel’s birth. Six years later, she still can’t bear to celebrate Samuel’s birthday on its proper day.

Things are strained in Amelia’s household to begin with. Both she and Samuel are troubled sleepers plagued by nightmares. Amelia dreams about her husband’s accident. But Samuel is haunted by a faceless monster. He can’t put a name to it; he just knows it’s there.

Every night, Samuel and his mother go through the ritual of inspecting his closet, peering beneath under his bed. And during the day, he practises magic tricks and fires off homemade weapons: “I’ll kill the monster when it comes, I’ll smash its head in!”

It’s all an attempt to protect himself and his mother from whatever darkness is descending, but it only adds to the mounting pressure on Amelia. Samuel is unruly, uncontrollable. He gets expelled from elementary school for endangering other children. His manic energy and incessant calls of “Mommm! Mahmmmmmmm!!!!” wear on her nerves, already fraught from chronic sleep deprivation. She’s quick to snap, even when he simply hugs her too hard.

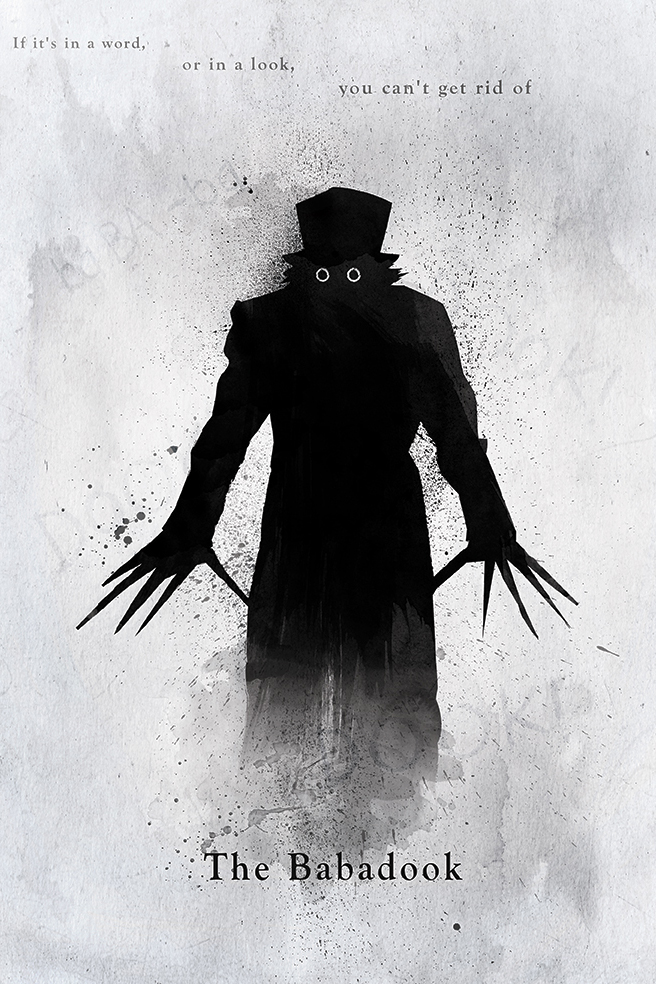

And then we meet Mister Babadook. “If it’s in a word or in a look, you can’t get rid of the Babadook.” Samuel finds him in an authorless pop-up book his mother hasn’t seen before; it’s been sitting on the shelf, out of sight, perhaps not out of mind.

The book is a brilliant way of introducing the film’s demon—a dark man in a top hat and black cloak who kills children in their beds. With its chilling yet artful illustrations and eerie, poetic writing, Mister Babadook creeps into the viewer’s psyche just as much it does Amelia’s and Samuel’s.

“You start to change when I get in, the Babadook growing right under your skin.”

Amelia quickly puts an end to the story, but it’s too late; Samuel knows what’s coming. As his obsession with building weapons grows, so does Amelia’s anger and frustration with her son. She insists that the monster isn’t real, but he’s certain that it’s only getting closer.

He isn’t wrong. The question is: Where does the Babadook truly reside? In their closets, cupboards and basement? In Amelia’s mind? Maybe in both.

That, to me, is the most intriguing part of the movie—its exploration of fantasy and reality, sanity and delusion. It reminded me a bit of Take Shelter, in how it asks the audience to decide, at least for a time, whether the threat is real or imagined, and in how it throws light (and shadow) on mental illness.

The Babadook isn’t afraid to show us something really scary, and its impact is profound and disturbing. In place of cheap thrills and gore, it uses imaginative, often abstract visuals. The film does a lot with its soundscape, too; whenever the Babadook stirs, we hear a chilling mix of repetitive sounds that are almost familiar, almost identifiable, like crickets at night or the electrical buzz of an unstable light bulb about to burn out.

Amelia tries to silence the noises by destroying the book, but the more drastic her attempts to bury it, the more fiercely it returns. “The more you deny me, the stronger I get.”

The Babadook becomes a metaphor for Amelia’s grief and depression. She’s stuck in the moment of her husband’s death, unable to process her emotions. She’s also suffocated by the guilt of blaming Samuel and the unease of her son standing in as her only companion.

Their relationship never crosses any sexual lines, but there’s a tangible discomfort from Amelia. At one point, Samuel bursts in on her in the night, interrupting an intimate moment while she’s alone in bed (there’s that electrical buzzing sound again…), and it highlights the strangeness of their dynamic—how Samuel’s birth brought about her husband’s death, effectively replacing one with the other.

As the world grows ever darker for Amelia and Samuel, we’re forced to wonder exactly what’s true. Amelia is being driven into psychosis through depression and sleep deprivation. And yet there he is, Mister Babadook—lurking in corners, scuttling and spattering across the ceiling like an insect or an inkblot, morphing, indeterminate, a Rorschach test. What is he? What is it? What does it mean to Amelia? What does it mean to us? And which demon would be harder to exorcise: the supernatural or the psychological?

The Babadook shows us that we don’t always have to eradicate our demons. Sometimes it’s enough to be aware of their presence and learn how to manage them. Because sometimes these things—in the shadows, in the mind—never really go away.