Archive for August, 2019

Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love

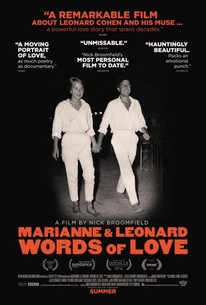

Sunday, August 18th, 2019—FilmMarianne & Leonard: Words of Love (USA 2019, Documentary/Music), Writer/Director: Nick Broomfield

Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love is a documentary about Leonard Cohen that’s framed around his relationship with Marianne Ihlen, a Norwegian woman he met in the 1960s when they were “almost young, deep in the green lilac park” on the Greek island of Hydra. Cohen was a writer on vacation, searching for inspiration; Ihlen was a single mother living there with her young son.

The pair fell in love and Cohen stayed on the island much longer than planned. Ihlen became his muse, the woman behind his songs ‘So Long, Marianne’ and ‘Bird on a Wire,’ among others. They were entangled in a relationship that lasted for years, sometimes together, sometimes apart.

I say that the documentary is framed by their relationship, because in spite of its title, the film ultimately focuses more on Cohen’s career than on Ihlen herself or even their love story. It’s not necessarily a bad thing; director Nick Broomfield shares insights and remarkable archival footage that reveal Cohen’s family life, his professional trajectory from skewered novelist to celebrated songwriter and poet, his internal struggle with becoming a performer, his years at a Buddhist monastery. Watching the film, you learn where certain lyrics originated, getting hints of how Cohen worked and what sparked his flames of genius—like the baskets of food and water Ihlen dropped over the Greek balcony while Leonard wrote, feverishly, fueled by speed and acid, in the drug daze of Hydra.

We do also get insider glimpses at what Cohen and Ihlen shared, and what it meant to him. Broomfield was briefly involved with Ihlen, and he does his research in gathering personal quotes and anecdotes about the famous couple. It’s a privileged perspective to open up to the audience, to the world. For me, it showed that Cohen may have romanticized his time with Ihlen. He continued to mention her at his concerts even after their split, and shows remorse to her through his writing (I have torn everyone who reached out for me. But I swear by this song and by all that I have done wrong, I will make it all up to thee). But was it really Ihlen or more the idea of her that appeared, for decades, to mesmerize him?

By the film’s account, Cohen wasn’t fully satisfied by his life with “Marianne and the child.” He felt the pull to return to Montreal, to live real life and seek new inspiration. (Well you know that I love to live with you, but you make me forget so very much. I forget to pray for the angels and then the angels forget to pray for us.) Gradually, he spent less of each year living with Ihlen, drawn by a need for connection with the transcendent—and other women.

Marianne & Leonard often alludes to Cohen’s many dalliances, including one with Janis Joplin. What he offered women was the ability to make them feel great about themselves, worshipped and adored, while in his presence. What he could never provide was the ability, or perhaps the desire, to make it last.

To hear Cohen’s songs, read his poetry, he seemed keenly aware of his failings, as well as both his vulnerability and power:

I heard of a man

who says words so beautifully

that if he only speaks their name

women give themselves to him.

If I am dumb beside your body

while silence blossoms like tumors on our lips

it is because I hear a man climb stairs

and clear his throat outside our door.

But also:

Do not forget old friends

you knew long before I met you

the times I know nothing about

being someone

who lives by himself

and only visits you on a raid

In his film, Broomfield pointedly highlights Cohen’s poem ‘Days of Kindness,’ including a reading by Cohen:

What I loved in my old life

I haven’t forgotten

It lives in my spine

Marianne and the child

The days of kindness

It rises in my spine

and it manifests as tears

I pray that loving memory

exists for them too

the precious ones I overthrew

for an education in the world

It made me wonder: Was the sacrifice worth it to Cohen? If he’d had the chance, would he have traded in that worldly education to stand by Ihlen and her son?

Even if he regretted the personal toll inflicted by his career and fame (and his gypsy spirit), was it worth it for the rest of us? For the millions inspired by his exceptional gift of words? I know more people who are deeply touched by his songs and poems than by any other artist. Who could un-wish Cohen’s lyrical legacy?

Finally, I wondered: Is it necessary, as the film suggests, for the great poets, filmmakers, singers to have that interpersonal distance—to be free, in their way—if they are to create truly magnificent art?

Marianne & Leonard reflects the sun-baked beauty of life on Hydra, of the countless artists who flocked there to sculpt and write and sketch. It also paints the island as a destructive place from which the human seeds that were sowed later unravelled; the children and spouses of open marriage, free love and rampant drugs found their way to addiction, suicide, mental illness. (Ihlen’s son wound up in an institution.)

For all Cohen’s extraordinary writing, he was, by many accounts, depressive, addictive and unstable. His words are eternal and painfully poignant. He was an otherworldly poet. But, to me, whether intended or not, the film makes a case for the poetry of everyday life: of cherished moments with family and loved ones, particularly the children who were never asking to be born, who deserve loving, reliable homes.

I don’t think Marianne & Leonard offers a fully realized portrait of Cohen. You don’t have to look far to find different interpretations of his personality, his character, his actions, and appraisals of his strengths and weaknesses, from people who knew him well. And, in framing the film around Ihlen’s role in Cohen’s life, Broomfield minimizes the singer’s many other friendships and partnerships, including his long-term relationship with Suzanne Elrod, the mother of his two children. (In fact, Broomfield all but ignores Cohen’s role as their father, and suggests that Elrod deliberately trapped him with their two children, while Ihlen had an abortion when she became pregnant with Cohen’s child, so he could be free. Was that really Ihlen’s motivation? Is that a fair depiction of Suzanne?)

Still, there’s a lot of wonderful material; Judy Collins, for one, provides enlightening accounts. And skewed or not, the intimate moments unveiled in Marianne & Leonard are something special, offering a hidden perspective that is rare to see of any couple, let alone one so mythical. Ihlen and Cohen famously passed on within months of each other, in 2016, both in their early 80s. She died first, of leukemia, and when Cohen learned of her condition, he promptly wrote her a letter. In one of the film’s most moving segments, Broomfield takes us inside her hospital room, showing footage of her reaction as a dear friend reads aloud Cohen’s last words of love to her. It’s an incredible thing to watch.

Whatever the true nature of Cohen and Ihlen’s relationship, their involvement has become legend, having inspired some of the greatest work by one of the greatest poets of all time. That makes Marianne & Leonard worth seeing for any Cohen lover.

* * *

Thanks to Kickass Canadian Lee Demarbre for bringing Words of Love: Marianne & Leonard to the Mayfair. It’s playing there again this week, if you get the chance to see it.